Tuesday, April 30, 2024

Review: "Playing for Freedom" by Zarifa Adiba

Translated to English via Susanna Lea Associates

English translation published May 2024 via AmazonCrossing

★★★

As a young music student, Adiba's concern was not how to find time to practice or whether she could afford a better instrument—both owning her own instrument and practicing at home were unthinkable. This was Afghanistan, after all, and music was at best distrusted. People who played music were distrusted. Girls who played music were distrusted. Adiba held fast to her dreams of playing viola for Afghanistan and for the world, but every day was a challenge.

In those days, writes Adiba, I had so little money that I couldn't even afford the ten afghanis (less than four American cents) it took to take the bus to music school. Instead, I walked for two hours every morning, from home to the ANIM, pacing along the damaged sidewalks of Kabul and crisscrossing the dusty city where high concrete walls had gradually sprung up in response to various threats, and to protect against explosions. (loc. 104*)

Adiba's story takes place before the Taliban took power in Kabul. She discusses this takeover at the beginning and end of the book, but for most of the book she is in an Afghanistan with some bare bones of possibility. Make no mistake: she had just about nothing easy. Start with being a girl in Afghanistan and add in poverty, and living with relatives who didn't want her family there, and a mother pushed to the breaking point by her own hard life—and then multiply that by, say, the pressure to get married to a man, any man, and turn away from any kind of freedom in exchange for a constrained and compliant life.

Everyone around me seemed genuinely hopeful that I would go with him, settle in his village, and stay locked in his house, having children and doing chores for the rest of my life. The worst part was my mother seemed delighted at the prospect, which only reinforced my despair and sense of abandonment. (loc. 1262)

It's a journey full of impossible choices. I wouldn't have minded a more chronological structure—it's largely chronological, but with frequent zigzags—or more about Adiba's daily life in Afghanistan: what home looked like, what a school day looked like, how it felt to leave the viola at school at the end of each day and pick it up again in the morning. Most of what I've read about Afghanistan is from the perspective of outsiders, and I'd have loved to see it better through Adiba's eyes. Her experience was unusual, too, in that although her family was poor she managed some travel, in and outside of the Middle East, while still quite young; among other things, she lived at various times in Pakistan, and I'd love to know more about how she experienced the differences of living there.

In many ways what interests me most is the way Adiba talks about her mother's life—with frustration, sometimes, and with hurt, because her mother was not always able to offer the kinds of emotional support that Adiba needed. But their stories are illustrative of two different ways in which women in oppressive societies struggle—Adiba, young and fighting to be allowed to follow her dreams; her mother, long since having lost sight of her own dreams and also unable to trust in her daughter's. It's a complicated story, and I'm glad it's been translated for an English-speaking audience.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Monday, April 29, 2024

Children's books: Role models: "Simone Biles", "Malala's Mission for the World", and "Sally Ride"

Malala's Mission for the World by Aida Zaciragic, illustrated by Ana Grigorjev

Sally Ride by Maria Isabel Sanchez Vegara, illustrated by Alona Millgram (Frances Lincoln Children's Books)

Simone Biles

Always nice to see stories of trailblazers and role models. You'd have to have lived under a rock for the past decade to not have any idea who Simone Biles is, but this is a great intro for young readers who are interested in gymnastics or other sports.

It's particularly interesting to me to see that the book alludes to recent scandals in the gymnastics world—in a very age-appropriate way—and also that it gives a nod to Biles taking some time off when the pressure was too much. It's easy to focus on the relatively simple things like gold medals (easy to understand!), but just as valuable, if not more, for kids to get messages about speaking up when something's not right and making sure to prioritize health. (And also nice to see the book say directly that Biles lived with her grandparents—I'm guessing that there aren't that many books where young kids who live with non-parental guardians can see their experience reflected in a neutral-positive way.)

All told, a nice addition to a child's library...especially one who tends to do cartwheels all over the furniture.

Malala's Mission for the World

I love seeing books for young readers about women making a difference in the world, and Malala Yousafzai is a great example. In Malala's Mission for the World, readers are introduced to her life in Pakistan and her passion for learning—and how quickly things changed for her.

The book is pretty text-heavy—better for more confident readers or read with an adult's support, but it allows for a lot more information and story than something briefer, so I'm generally on board with it. The illustrations are beautiful, but the text has its fair share of errors, awkward constructions, and presumably accidental repetitions. I do wish the book had been more carefully edited/proofread, because that would have made it a much more useful tool for kids working on language and vocab skills as well as learning something about (recent) history, other countries, and women in the world. Overall a thoughtful and age-appropriate read, though, and I'm glad to see that Malala's parents are also highlighted as proponents of education and equality for girls.

Sally Ride

What a delightful look at one of my favorite figures from women's history—well, history more general, but Sally Ride was an absolute trailblazer for women. Sally Ride takes young readers through her life, from her interest in science from a young age to the company she started with her partner, Tam O'Shaughnessy.

I vaguely remember the media about Sally Ride when she died, and when the fact that she was in a long-term relationship with a woman became public. I'm glad that this book mentions it, and casually at that. This is part of an extended series of biographies of famous people by this publisher, and they're clearly putting in the effort to make sure that diversity doesn't get lost in the shuffle, from making note of LGBTQ folks in history to ensuring that there's representation (is that an artificial leg I see?) in the illustrations. The text is on point, and the illustrations have lots of little details to find. It would make for a wonderful book for early readers who are interested in science.

Thanks to the authors and publishers for providing review copies through NetGalley.

Saturday, April 27, 2024

Review: "Bloodlines" by Tracey Yokas

Published May 2024 via She Writes Press

★★★

Yokas's life was upended when her daughter got sick—anorexia and depression that would leave the family scrambling for answers and solutions and her daughter shuttled from one programme to another. In Bloodlines, Yokas describes her experience with that scramble: fear and trauma and figuring things out; learning a new language for what her daughter was going through and trying to make it clear to her husband that mental illness was not a choice and not their daughter trying to punish them; wrestling with what it means to be trying to get your child through an eating disorder when you are still struggling with your own relationship with your body.

I appreciate the note at the end where Yokas says, directly and clearly, that she had her family's permission to tell this story—not that I had reason to think otherwise, but memoir is a tricky thing; there's the rare person out there who can write a memoir that is only about themselves (like...I've read more than one memoir by people who went and marooned themselves on desert islands), but mostly memoir involves telling not only parts of your own story but, necessarily, parts of other people's stories. Sometimes the line of what is yours to tell and what is not is crystal clear; sometimes it is fuzzy. I'm always glad when writers recognize and address that balance, whether that means seeking permission or intentionally leaving out details that might affect other people. (And, well. Sometimes it means addressing it and then telling your full story anyway. I cannot really relate, but I am quite certain that there are times when it is the best option.)

The book moves through something of a frenzied desperation to fix things, and despair, and eventually an unsettled acceptance that you can't fix everything...and sometimes, compromise is the best you can hope for, and that's okay. The book takes place (more or less) in California, though to me it felt inexplicably midwestern. It's straightforward writing, but I think it's at its most interesting when Yokas talks about knowing something intellectually but having trouble applying it in real life—knowing that a child struggling with an eating disorder probably doesn't need to see a parent on a diet, knowing that asking kids to censor themselves when talking about their family with outsiders is not a sign that all is well—because that's something that we probably all come up against at some point or another (or all the time!), but it's not something I see written about all that much.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Thursday, April 25, 2024

Review: "Full of Myself" by Siobhán Gallagher

Published April 2024

★★★★

Some of the messages Gallagher got growing up: Thin is better. Conformity is better. Your body is not right. You are not right.

In Full of Myself, Gallagher talks about growing up uncomfortable in her body—or, more to the point, being made to feel uncomfortable in her body—and what it meant to be a young woman in an image-driven society that both sexualizes and shames girls. The pop culture references will probably land best with millennials (why hello there), but I love the "years in fashion" pages—they'll feel retro to a younger crowd, but millennials, take note, the closet of your past is calling.

Gallagher's art style is generally pretty simple, but I really like the way she draws herself. Lots of expression in a few simple lines of the face. I wondered, reading it, how differently this book will ring for someone who is plus-size versus someone who is straight-size—it'll be relatable to anyone who has struggled with body image and/or an eating disorder, but frankly probably more relatable to people who have spent more time on...let's call it the thinner side of the American average? No criticism here, just guessing that it will feel different for someone who is a size 8 vs. a size 18.

Three and a half stars, and I'd be curious to see what sort of fiction Gallagher might come up with.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Review: "Pillow Talk" by Stephanie Cooke and Mel Valentine

Published April 2024 via HarperAlley

★★★

In Toronto, Grace is confident as a student, but not so much in the rest of her life...until she's introduced to the Pillow Fight Federation (PFF) and reincarnates herself as Cinderhella, a competitor to be reckoned with in the ring.

I love roller derby (watching, not playing), and I suspected that this would have a similar vibe—and indeed, the PFF of this graphic novel reads like a cross between roller derby and wrestling. Think all the drama of a wrestling match (and wrestling personas) mixed with the supportive environment of roller derby...and with the athleticism of both. (I learned from this book that professional pillow fighting is in fact a thing, and I'm ten percent disappointed that it's not a work of the writer's imagination but 90% delighted that, you know, it exists.)

Grace struggles with confidence and body image throughout the book, and I love love love that 1) while these things are matters of discussion, there's never a point at which anyone—including Grace—puts the focus on weight loss and 2) the answer to the riddle, so to speak, is not 'finding someone who's into you will solve your confidence problems'. Among other things, this keeps the book feeling fresh.

I'm not as sold on the artwork, which is competent but generally feels more 'comic book' than 'graphic novel' to me in style; partly that's the way the characters are drawn and partly it's how many of the backgrounds are either very simple line work or plain with a simple gradient. I'd also have loved to see a bit more of a journey for Grace as a pillow-fighting athlete—she's good from the very beginning, and as nice as it is to see her succeed, it also feels more relatable (and realistic) to see a character have more ups and downs with their new sports etc. But if you're a comics reader—or a roller derby enthusiast—this is worth the read.

Thanks to the authors and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Wednesday, April 24, 2024

Review: "Girl Abroad" by Elle Kennedy

Published February 2024 via Bloom Books

★★★

You know the drill: very average girl lands in London to spend a year abroad, having reassured her overprotective father that her flatmates are all nice-sounding girls…only to find that said flatmates are boys. And hot boys, at that! And one of them makes her feel tingly! Not to mention the Bad Boy, Not a Flatmate but Has a Motorcycle, who also makes her feel all tingly…and the older guy, a rando member of the aristocracy, who wants to introduce her to his high-flying way of life. What’s a girl to do?

Date all of them, naturally. While telling her father that yes, yes, her flatmates are all nice girls! And she’s not boinking any of them. Definitely not.

Now, I’m not sure if this counts as a reverse-harem book or just some sort of wish fulfillment (I’m far more familiar with the latter than with the former). Audience-wise, it’s more new adult than anything, but I don’t have (or want) a Goodreads shelf for that, so…let’s call it romance. Think normcore heroine who inexplicably has (almost) every boy she meets falling at her feet; think romantic options that are conveniently simplified to Boy Next Door (translation: hot, nice, has an accent), Bad Boy (translation: hot, has a motorcycle, likes Netflix and Chill), and Badder Boy (translation: hot, rich, not-so-secretly sleazy). The configuration of love interests is careful; it's not an accident that Abbey has the hots for one flatmate and one and a half non-flatmates (or that the flatmate who sleeps with anything that moves is the only straight man in the story to not fall head over heels for her), because that limits the amount of bad vibes between flatmates when she eventually has to choose. (I did find it odd that, in a book with a fair amount of boinking—new adult and all that—we see more boinking with the guy she doesn't end up with than with the guy she does end up with. Not that it matters, just...seems a bit odd.)

I liked the side-plot mystery—the resolution was convoluted at best, but it was a nice little bit of interest between boy dramas. But...it's not really enough to keep Abbey from relying on her father's rock-star stories to be interesting to other people (usually immediately after swearing that she won't tell people who her famous father is), and not really enough to keep the book focused on anything other than romantic drama. Obviously it's meant to be heavily about romantic drama, so that will work well for many. I think I was just looking for a bit more depth for all the characters...and I wouldn't have been sorry if romance had been scuppered entirely and the focus had been on random historical mysteries.

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

Review: "Rift" by Cait West

Published April 2024 via William B. Eerdmans

★★★★

I'd been told that the world was dangerous for women, writes West, that being out of the protection of my father would be asking for harm. A woman alone was an easy target. I was an easy target. But I ventured out into that danger anyway when I left my parents' home, and with it the Christian patriarchy movement. Only later did I realize how much danger I'd left behind. (loc. 1724*)

When West was growing up, the rules were relatively simple: she would be a child until she married, and who and when she married (and whether she married at all) would be up to the discretion of her father. Under Christian patriarchy, girls were to be silent homemakers-in-training who submitted to their father in everything, and women to be homemakers and mothers who submitted to their husbands in everything. It was a long time before West started to question this.

Under a courtship model of "romance", romance itself was entirely out of the question: West was to keep her emotions strictly in check while she had structured, chaperoned conversations with a potential suitor and had equally chaperoned dates. When a suitor moved away, they wrote letters and emails: When Matthew's letters came in the mail, my father would open them and read them first, to make sure there was nothing inappropriate or overly emotional in them. ... Before I send him my replies, I gave them to my father, so he could make sure I wasn't having any romantic emotions. (loc. 959) Emotion was supposed to come later, only after betrothal or (better) marriage; this was supposed to protect West, to protect girls in general, from broken hearts and loss of purity. Nobody asked the unmarried "girls" whether they wanted to be protected in this manner. Nobody asked the married women whether this model of courtship had brought them the type of relationship they wanted.

Religion is largely beyond the point in West's book. She writes instead about power and control and of course rifts—rifts in family, rifts in culture, rifts in landscapes, rifts in understanding of the way the world was shaped. In later parts of the book the story feels a bit more scattered, which is not unusual for a book that is mostly about being in a particular thing and partly about being out of that particular thing, but she writes with a great deal of thoughtfulness about the ways in which her father's chosen way of viewing the world impacted those around him. I'd be curious to know more about how her mother and sister experienced this patriarchal culture—her sister in particular, because the shift to courtship happened only when her sister was very nearly an adult, and would otherwise have been very nearly free. (Those are, of course, their own stories to tell, but I am curious nonetheless.) It's a fascinating look into a world that I want no part of—West was lucky to make it out on more or less her own terms, and hers is one of so many recent voices speaking against the ways in which the Christian patriarchy (and the patriarchy more generally) acts to tear apart women's agency and freedom.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Sunday, April 21, 2024

Review: "Betty & Veronica: Senior Year" by Jamie Lee Rotante and Sandra Lanz

Published October 2019 via Archie Comics

★★★

I read piles of Archie comics growing up, so I occasionally get curious about these updated versions. Not quite nostalgia reads… In Betty & Veronica: Senior Year, B&V have finally (you guessed it) made it out from junior year and into their senior year at Riverdale High. (For context, if you didn’t read quite so many of these as I did growing up—the characters are perennial juniors, old enough to drive and hold the occasional part-time job but not yet worried about things like college and the real world.)

For the sake of this book, Archie is—very intentionally—out of the picture. Whatever fighting over him Betty and Veronica did is in the past; as the book opens, Betty and Reggie have just split up, and Veronica doesn’t seem all that interested in dating. Archie is in the background, but neither Betty nor Veronica is interested in continuing to fight over him. What they are both interested in: college. They dream of going to the same place, the local university (where Betty can get a full ride and Veronica can earn admission without nepotism)…but then they both start to realize that no, this university is not their dream. And neither of them wants to tell the other.

It’s interesting to see this more updated take. In some ways it’s more realistic (e.g., there’s a scene in which one of the girls gets drunk, which would never have happened in the original comics), and in other ways…well, I guess it’s not all that unrealistic for a nepotism-child to have far more responsibility at her father’s company than a teenager should have.

The art is a bit of a departure from the originals, which I don’t always love but also makes a lot of sense—it’s in keeping with the more grown-up feel of the book. Overall, it does make me think that it’s too bad that even in the B&V-focused comics of yore, the emphasis was so often on chasing Archie.

Saturday, April 20, 2024

Review: "Not Your Average Jo" by Grace Shim

Published March 2024 via Kokila

★★★

It's a really bad sign when there's a typo in the first sentence: When you're an Asian Americn... (1).

Fortunately the state of the proofreading improves from there, but the book fell a little flat for me. It's ambitious, tackling microaggressions and overt racism along with the nepotism of the entertainment industry. But the only character who's fully fleshed out is Riley, the main character, and she's not awfully likeable. She's a high school senior but feels more like a fifteen-year-old in maturity (pro tip: a school-wide performance with people who can make or break your career is not the time to throw a tantrum—even if you're right about the things you're tantrum-ing about), and just kind of inconsistent. Her fancy LA boarding school isn't much better (they can give out all room assignments ahead of time but don't know who your roommate will be until you move in...?), and I never figured out what the school's goal is—the entire goal for Riley seems to be to get a record deal with a band she's been assigned to without her prior knowledge (working with people she doesn't particularly like, some of whom are blatantly racist), and there's never any suggestion that she might have other goals for herself, or that the school might support other options, etc. The book treats this largely as a question of racism (Riley being used to prop up white students' future careers), and while that might be part of the case, it's also a bigger (unaddressed) issue for the school.

So...well intentioned, and I'm glad to see such a direct discussion of anti-Asian racism, but not really the book for me.

Thursday, April 18, 2024

Review: "Siblings" by Brigitte Reimann

Translated from the German by Lucy Jones

English translation published March 2023 via Transit Books

★★★

It’s 1960 in East Germany, and Elisabeth is sure she knows what is true and what is right: the East German state. Her brother, Uli, is not so certain—and not long after the book opens, he confesses to Elisabeth that he plans to defect to the West.

This was first published in East Germany in the early 60s, which tells you a few things straight off—that the East German censors approved it, for one, and that it will thus maintain a position that was palatable to those censors. I didn’t read up on the book or the author until after I’d finished reading the book itself, and I have to say that the commentary on the book is perhaps more interesting than the book itself. This vivid and intriguing novel, writes John Self for The Guardian, published in 1963, is a largely autobiographical story by an author who had a short, eventful life, marrying four times and declaring her intent to live “30 wild years instead of 70 well-behaved ones”. She made it to 39, dying in 1973 from cancer believed to have been caused by inhalation of pollutants in her role as a state-sponsored artist at an industrial plant.

The primary relationship of the book, between Elisabeth and Uli, is an odd one, more than a little uncomfortable for its not-quite-incestuous undertones. Elisabeth loves her brother above all other men and defers to his judgement when seeking out new conquests; they take it in turns to be jealous over each other’s relationships and to make odd comments about, e.g., how good people of the other sex smell. I cannot say that I particularly enjoyed their relationship, or Elisabeth’s character (she’s a bit shouty), but I’m fascinated by a representation of East Germany in which the narrator believes (or wants to believe) in the state and does not want to leave.

How much of this is autobiographical requires some guesswork, of course, but it’s not hard to think that Elisabeth is a fairly close stand-in for Reimann. She began writing the book after her brother defected—in the early days of East Germany, when the Berlin Wall was yet more a concept than a fact—and so too does Elisabeth face a factory job and a brother (two, actually) who thinks there is a better future to be found elsewhere. Elisabeth, who is something of an artist in residence at a small-town factory, clearly thinks herself one of the proletariat but is still perhaps too bourgeois for the state. (It does not, perhaps, occur to her that as an artist in residence she is in a very different position than, say, the workers who have been assigned to do backbreaking manual labour at this factory.) And yet that never bothers Elisabeth: she is perfectly ready to shout at her bosses (they are in the Communist Party; Elisabeth was not, and nor was Reimann) when she thinks they are in the wrong, and she has a pretty rosy view of what taking her concerns to higher-ups will lead to. And, of course: because this is a book written by a staunch supporter of East Germany and approved by the East German state, she finds that she is more or less in the right.

Joanna Biggs notes in a New Yorker article that this translation was done after the uncensored manuscript was found by chance last spring [in 2022], which does make me wonder how much this version differs with the German version published in the 1960s. I have to wonder, too, how differently Reimann might have ended up viewing things had she written this later, after the physical Berlin Wall went up and separation was starker, and/or had she not died so young. Would she still have been championing the East German state had she written this in, say, the early 1980s? It’s impossible to know. I imagine, though, that her choice to give her narrator two brothers—one lost to the materialism of West Germany, one yet redeemable in Elisabeth’s socialist eyes—is reflective of how Reimann viewed the reality of her own brother’s choice versus what could have been.

I’m now curious about Franziska Linkerhand, which was written later and might answer some of my questions, but I don’t think it’s been translated, and realistically…I’m not curious enough to struggle through 600+ pages in German, lazy member of the bourgeoisie that I am.

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

Review: "The Last Girl Left" by A.M. Strong and Sonya Sargent

The Last Girl Left by A.M. Strong and Sonya Sargent

Published April 2024 via Thomas & Mercer

★★★

Five years ago, Tessa was the sole survivor of the worst crime Cassadaga Island has ever seen. Since then, she's been struggling to keep her head above water. As a last-ditch attempt to finally put the murder that killed her friends behind her, she decides to take the biggest leap she can—to rent the same house. For a month. In November, and on an island—with no easy way off. The murderer is dead, and so it should just be her friends' ghosts haunting the place...but something is not...quite...right. I read this partly because it reminded me of Riley Sager's Final Girls. Not sure what it is about human nature that makes it appealing to read about someone who has already survived something horrific again being subjected to, well, something horrific, but a well-done thriller set in an isolated house is deeply satisfying (and I can't be the only one who thinks that way, or...books like this wouldn't exist).

The book is a little slow to get started—Tessa's interactions with her sister read rather like throat-clearing en route to the bulk of the story—but once she's on the island and back in the house things pick up. I wondered at times whether bringing Tessa's sister to the island might have upped the stakes, but having Tessa be so isolated definitely upped a different kind of stakes. There are some solid red herrings in place, but in a way that doesn't feel too surprising when we learn the truth (a good thing—I'm not a fan of mystery resolutions that come out of nowhere). I had my suspicions, some but not all of which proved correct, but the exact details are locked up well enough until the reveal to keep the reader guessing.

In places I'm not fully convinced: first, I think the tension could have been ramped up even more before the climax. It's a long simmer before an abrupt boil, and I wonder whether that could have been heightened by, e.g., Tessa gradually remembering bits and pieces of what happened five years ago. (She gets flashbacks, but it's not really presented as an experience of putting things together.) I'm also on record many times as not liking Evil Villains Who Are Evil, and...we have one of those here. And finally, I'd like to know if the original investigators ever did, you know, the slightest shred of investigating, because (vaguesauce to avoid spoilers) it seems that they missed some pretty major things.

With that in mind: if you're into thrillers set in isolated locations, and final girls trying to survive yet again—not to mention things that go bump in the night—this is a very solid quick read of a book. Maybe don't take it on your next beach vacation...

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Monday, April 15, 2024

Review: Longfom essay: "My Mother and Other Wild Animals" by Andrew Sean Greer

Published April 2024 via Amazon Original Stories

It had been years since Greer and his mother went on a holiday together—since Greer was a teenager, in fact—and so, when she proposed visiting him at his short-term writing appointment, he proposed a road trip. She leaned more staid, so he committed to making the trip as low-key zany as possible: odd roadside attractions, unique hotels, and egg costumes, anyone?

The resulting story makes for a short and feel-good essay about making memories while it's still possible, whether that means planning your own funeral while still in robust health or, you know, driving halfway across the country on a whim. Greer avoids putting too much emotion or depth into this, keeping it light and playful even when talking about more serious things, but it's a lovely tribute to his mother and sounds like an even better experience to share. (Also, the long-standing friendship his mother has with Judy sounds fantastic, and like the sort of friendship everyone should seek to cultivate with someone they love.)

This is probably best recommended for people with a Kindle Unlimited subscription (I believe most Amazon Original Stories are available there), and perhaps as fodder for planning your own relaxed mini-adventure.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Sunday, April 14, 2024

Review: "Freshman Year" by Sarah Mai

Published February 2024 via Christy Ottaviano Books

★★★

Oh, the trials and tribulations that come with freshman year: <i>Freshman Year</i> follows Sarah through her first year at university as she goes through the usual experiences: roommates and dorm adventures and too much homework and drinking and being sort of independent for the first time. As I understand it, this is a fictionalized version of the author's own experience, but it will be recognizable to just about anyone who has gone off to university.

The book is very well drawn; the story is far more character-based than plot-based. It's not that there's no plot, but in a lot of ways this is everywoman's journey through the (American) university experience, and so the plot tends to stick to small-scale things. I'd probably have appreciated this quite a lot as a teenager, but as an adult I found it rather slow going. (I read this over a couple of weeks and may have missed some things, like why Sarah's mother uses a wheelchair—I thought MS but then she says something about relearning to walk, which makes me think accident—or why Sarah has been to so many funerals.) The quality is there, just not quite what I'm looking for in a graphic novel at this time. Recommended for teens, especially those who have a bit of trepidation as they head off to college.

Friday, April 12, 2024

Review: "The Taken Ones" by Jess Lourey

Published September 2023 via Thomas & Mercer

★★★

Three girls go into the woods—but only one comes out. Decades later, a woman is discovered—minutes too late—buried alive. The cases shouldn't be connected...but it's clear immediately that they are. On the case is Van Reed, a cold case detective with a lot to prove, and things will get messy before they start to make sense...

I find cold cases fascinating—both real-life and fictional—so I'm fond of them in mysteries. This story felt like it had a layer too many, though: Van has a childhood trauma backstory (practically de rigeur in mystery series these days), and there's that thing she did as an adult, and there's the way she was run out of her previous department. Oh, and she's psychic.

Paranormal twists never really do it for me (they take me right out of the story), and I probably wouldn't have read this if I'd known there was the psychic angle. As it is, I think I'll pass on further books in the series; the multiple tragic backstories would have been more than enough, but the psychic thing is just a bridge too far for me. Add to that my dislike of chapters by Evil Villains Who Are Evil, to say nothing of Evil Villains Who Are Evil And Also Clearly Deranged, and this is just not the series for me.

Thursday, April 11, 2024

Review: "The Limits" by Nell Freudenberger

Published April 2024 via Knopf

★★★

It's 2020 in New York, and things are not going especially well. Kate is preparing to parent a baby but not especially prepared to suddenly parent a stepdaughter she's never met. Pia, said stepdaughter, would rather be back in Polynesia. Across town, Athyna is logging in to Kate's English class when she can, but her attention is divided, as she's suddenly been given most of the care duties for her young nephew. And half a world away, in Mo’orea, COVID has barely registered for Nathalie, Pia’s mother, other than to help determine which part of the world Pia will be living in.

The Limits is set during the relatively early days of COVID, partly as a plot device (among other things, COVID gets Stephen out of the apartment and makes Athyna's walls close in on her) and partly as a reminder of different shades of privilege. (It is not lost on me that it is lost on Stephen that his surprise at Athyna being so quiet is—in the context of the scene—implicit racism; nor is it lost on me that it is, again, lost on Stephen that a teenage girl might be uncomfortable being told to spend the night in the house of a man she’s never met.) It’s well written and thoroughly thought out, though readers should go in expecting a relatively slow read. I was a little surprised by how little interaction Kate in particular ends up having with the rest of the characters—they’re all operating, on some level, on their own planes. But I love the push-pull between how we see Kate and how we see Nathalie: neither is the villain in the other’s story, but they’re each a little skeptical of the other, and the way they perceive themselves is contrasted by the way they see each other.

I read this for the description, but rereading that description now, I'm not sure how well the content of the book actually matches it. The description feels aspirational, maybe, in retrospect? Or perhaps like a "find the six items that are different in these pictures" game. The description calls Athyna's nephew a toddler, but in the book he's four (still in need of a ton of attention, but no longer a toddler); in the description, Pia and Kate are in "near total isolation" together, except book-Pia spends as much time as possible outside the apartment, so they rarely interact; and so on. Not quite wrong, and not bad, just...a little off-kilter.

This is a book in which not all that much changes for the characters as they make their way through a few months of COVID-induced uncertainty and events both predictable and unpredictable in their own lives. Maybe they come out a little more jaded or with their eyes a little wider open, but on the whole of it the characters come out of the book as the same people with the same views that they went in with, just with an extra few months of experience. A solid read, if not one that left me deeply invested in what becomes of the characters after the end of the book.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Tuesday, April 9, 2024

Review: "Between Two Trailers" by J. Dana Trent

Published April 2024 via Convergent Books

★★★★

A preschooler's hands are the perfect size for razor blades, begins Trent. I know because I helped my schizophrenic drug-lord father chop, drop, and traffic kilos in kiddie-ride carcasses across flyover country. (loc. 88*)

There's an opening to capture the attention if ever there was one. Growing up in Indiana, Trent was schooled from a young age in life lessons: if you kill somebody, do it in Vermillion County; there's only so much sugar in the sack; natural elements are the best weapons; never trust a liar. Her father was convinced that these lessons would not just keep her safe but make her strong, and her mother's focus was primarily on ruling the trailer from the nest of sheets and blankets she built up in bed. They loved her—but theirs was not a conventional love.

Dad, too busy to bother with me before I could walk, used duct tape to fasten my hands to my baby bottle filled with chocolate milk. I sat on the kitchen counter by him all day, lifting that duct-taped bottle to my mouth and catching his marijuana exhales as weed ash fell onto his open King James Bible. (loc. 113)

Between Two Trailers sees Trent through those young years of drug-running in Indiana (the right age for those kiddie rides: "That ain't no toy!" her father yelled (loc. 1033)) and off to North Carolina, where her mother relocated the two of them on a whim. A trailer her mother called a shotgun house because if our enemies sent twelve-gauge buckshot through the kitchen window, we'd drop like dominoes (loc. 103); ceiling tiles razored to pieces as her father searched for government bugs; apartments in North Carolina subsidized by the extended family as her mother's fortunes—and get-up-and-go—fluctuated.

It is King and the Lady, as Trent refers to her parents throughout the book, who set the scene and rule the roost throughout the book. King and the Lady who define what normal is throughout Trent's childhood and King and the Lady who compete for Trent's affections and future. The book slows down a bit as Trent gets older and dives headfirst into as ordinary a life as she can create for herself and as she moves away from the lessons of her childhood. It's clear, though, that however complicated a childhood it was (and oh man—it was complicated), Trent has come to make peace with that childhood and to embrace her parents for who they were.

Thanks to the author and publisher for inviting me to review this title through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and pay not be final.

Monday, April 8, 2024

Review: "Sisters of the Sky" by Lana Kortchik

Published February 2024 via HQ Digital

★★★

War is upon the Soviet Union, and there’s nothing Nina can do about it—until a women’s aviation regiment is formed, and she has the chance to join. War was personal before, but now it is desperately, painfully close, with not only Nina’s family to worry about but also her new regiment.

I’m familiar with Raskova’s regiment because of other books, and I’ve always found it fascinating—there were so many problems with the Soviet Union, but they were also the only major player in WWII (I don’t know about minor players) allowing women to fly in combat (or just more generally to take combat roles).

Plot-wise, the book does sometimes feel like it’s trying to hit all of the known key points from this regiment rather than focusing more closely on a specific experience. Nina is right in the thick of things, learning to respect (and earning the respect of) Raskova and staunchly optimistic about the importance of their flights even as her best friend’s courage crumbles. In some ways I think Katya’s experience is more relatable, and more interesting: it’s not exactly uncommon to see stories of people who are heroic and brave and willing to put it all on the line; Katya, meanwhile, is so clearly miserable to be away from her young daughter, to say nothing of her peacetime life, and while she’s treated as less brave (and certainly less fun to be around), I have to say that I…can’t blame her. Even as a non-parent I have to think that the decision to leave your child in the middle of a devastating war (with not just violence to worry about but also starvation, etc.) to go fly perilously dangerous missions (with no guarantee of return, or time frame for return) would be…difficult. Katya’s not a particularly sympathetic character, and hers is not a story that usually gets told, but hers is the story that might resonate most.

The book is more about friendship than about romance, but there is a romance thread. I ended up wishing that instead of that thread, and all its messy tangles, we’d had more about the other women in Nina’s squadron. We get a bit about them, of course, but other than Katya they largely stay out of focus. Still, I always love seeing more about this bit of history and the stories that don’t always make it out of the footnotes of history books.

Sunday, April 7, 2024

Review: "The Morning After" by Kate William (created by Francine Pascal)

Published 1993

★★★

Well. I've jumped back in eighty or ninety books down the line, because I remember this mini-series about Margot the Psychopath (as opposed to Jessica the Sociopath), and...I don't have a lot of readerly self-control. So here we are. Spoilers below, if you're worried about, you know, spoilers for book 95 of a series published thirty years ago.

The Morning After opens not too long after a terrible prom-night car accident that may or may not have taken place in a previous book. (I can't find mention of it in the previous books' descriptions, but you never know—Sweet Valley is absolutely enough of a soap opera setting that it's possible that a new-stepsister-for-a-side-character could be a main plot and a car accident that kills Jessica's One True Love could be the B plot.) It's not entirely clear what happened, just that Elizabeth might or might not have been driving, and now Sam is dead, and Jessica blames Elizabeth wholeheartedly...even though Jessica knows things about that night that even Elizabeth doesn't know.

No, Jessica told herself. Don't think about Liz. Elizabeth had been driving the Jeep that night. What happened before they got in the car didn't make any difference. It was Elizabeth who killed him. (107)

Guys. Jessica does not even speak up to tell the truth when Elizabeth is arrested for manslaughter. Partly because she's scared of the consequences, but also because she's still mad at Elizabeth for "stealing" Jessica's boyfriend—read: for leaving the dance with him. Is there any evidence that Elizabeth and Sam were romantically involved? Nope. Would anyone who's ever met Elizabeth reasonably think her capable of trying to "steal" Jessica's boyfriend without perishing of guilt? Nope. Would anyone, including Elizabeth, doubt that trying to do so anyway would result in Jessica promptly shoving Elizabeth into a busy highway? Nope. Has Jessica repeatedly tried to steal Elizabeth's boyfriend? Of course. (Elizabeth's boyfriend Todd, incidentally, is as usual inclined to believe the worst of Elizabeth and has been avoiding her instead of, oh, showing any sympathy for the fact that she was just in a deadly car accident and may or may not have been behind the wheel.)

Anyway. Side plots abound: Lila is still very traumatized from attempted rape in what looks like book 90, but when she is further traumatized, the general opinion at school is...well. Bruce suspected she had made the whole thing up; Lila had always been a tease (9). Honestly, the slut-shaming and trauma-shaming in this series is unreal; later, when Amy hears who Bruce is "in love" (in the most 1990s teenaged sense of the word) with, this is her reaction: "Do I know her? Everybody knows Pamela, if you know what I mean!" She winked at Maria, who rolled her eyes (93). This is extremely on-brand for the series (remember book 1, when Jessica let everyone think that Elizabeth had gone out with a Bad Boy and come home in a police car, and everyone—including Todd—decided Elizabeth was a slutty slut who deserved every bad thing that came her way?), but good god. Never mind that Bruce is perfectly happy to sleep around himself, or that he has only been on about two dates with this girl—when he hears that she's not pure as driven snow, he casts her off as another slutty slut and spends the rest of the book (and at least half of the next one; stay tuned) feeling butt-hurt about it.

Sigh.

And then we get Margot. Margot, who is a pretty minor part of the book but the whole reason I am rereading this little mini-series. I'd actually forgotten that the A plot here is about Elizabeth being arrested for manslaughter—what I remember is Margot smirking as she encourages her foster sister to dig a butter knife into the toaster and thus set the house on fire. This is not a girl you want to mess with, because Margot wants what she wants...and she's willing (nay, happy) to kill to get it.

Saturday, April 6, 2024

Children's books: Parents: "Always Carry Me with You", "I Love You", and "Call Your Mother"

I Love You by Mary Murphy (Happy Yak)

Call Your Mother by Tracy C. Gold, illustrated by Vivian Mineker (Familius)

Always Carry Me with You

I'm not sure if this is a science lesson hidden within a love letter or a love letter hidden within a science lesson, but either way, it works. In Always Carry Me with You, a father tells his daughter all sorts of cool things about rocks...and then compares his love for her to a rock, something she can carry in her pocket as a reminder that it's there.

It's sweet any way you slice it, but honestly, the first audience I thought about for this was children whose parents are terminally ill or otherwise facing an uncertain future. I don't mean this in a maudlin way (and obviously the book is perfectly appropriate in happier contexts!), but I imagine that one thing you'd want to do in that scenario is find ways to support your kid even after you're gone...which might include giving them a way to carry your love with them. (Just, uh. Make sure they know that it's not just one specific pebble that'll do the job. Kids lose things. Adults lose things.)

The drawings are playful (and somehow feel very French?), with more than enough whimsy to keep kids looking. The font feels like an afterthought, but that seems like a pretty minor objection, all things considered.

I Love You

What a sweet book. Reminiscent of "My Favorite Things" from "The Sound of Music", I Love You shows an adult and a baby panda romping through fun activities—each of which is a new way to tell the baby panda that it is loved. I love you like / a crayon drawing dragons, promises the book, and in turn I love the creativity that has gone into each choice.

The illustrations here are simple but high-contrast, with enough detail to keep readers entertained...and pandas that look truly snuggly. This is definitely one to be read aloud—young readers might enjoy it alone, of course, but it'll be at its best when it's not a solo endeavor; I'm willing to bet that the author made a point to read this aloud throughout the process of writing to check the flow and rhythm of the book. An excellent addition to an early reader's bookshelf.

Call Your Mother

You know the refrain here already: Call Your Mother. This deceptively simple picture book takes readers through a series of times a child might call its mother—from infancy (I don't have kids, but the exhausted mother stumbling in in the wee hours of the morning made me laugh with sympathy) through to schoolday nerves (my gosh that hug looks cozy) and into adulthood.

I think parts of this will resonate better with adults, who can perhaps remember each of these sorts of incidents better than a young reader can imagine, but I can also easily see it as a way to remind an anxious kid that their parent(s) will (...barring the unexpected, but maybe an anxious five-year-old doesn't need to hear that...) be there for them as they grow and age, in good times and in bad. My favorite illustration, far and away, is a variation on the cover illustration, but the whole thing is neatly done, with clean and soft lines. Would absolutely put this one on a young kid's shelves.

Thanks to the authors and publishers for providing review copies through NetGalley.

Friday, April 5, 2024

Review: "Just Perfect" by Hanne Arts

Published 2014 via CreateSpace

★★

A valiant effort but the work of a relatively new writer. Just Perfect is trying to cover a lot of topics—bullying; family dysfunction and alcoholism; teenage relationships; anorexia. Unfortunately it struggles to hold on to more than one of these threads at a time, leaving the work feeling full of loose ends. Christina's eating disorder (which appears more or less out of nowhere, with her feeling no effects and attracting no attention until she is at a heart-could-stop-any-minute low weight) is a mix of On Death's Door and wildly incompetent care à la 'Well, you're perilously unwell but you can probably handle this at home on your own, hmm?' Consistent with a lot of teenage writing (consistent with my writing when I was a teenager), Christina's voice leans heavily into angst.

I see that there's a sequel—I will not be seeking it out, but hopefully it has a bit more balance.

Thursday, April 4, 2024

Review: "Every Time You Hear That Song" by Jenna Voris

Published April 2024 via Viking Books for Young Readers

★★★★

She told me it was okay to take it slow, that everyone learns at their own pace, but my pace is wildfire. My pace is lightning and luck and all the desperate longing of the universe. (loc. 161*)

In the early 1960s, Decklee has a dream, and she'll do anything to make it come true—even if that means losing everyone she loves.

People never talked about Decklee Cassel being from Mayberry unless it was to compliment her for getting out, because here's the truth: no one cares about towns like this until they're behind you. (loc. 238)

And in the present day, Darren is convinced that she's made for more than Mayberry, the same small town Decklee grew up in. She won't destroy everything in her path to get out...but she will go on a quest to find Decklee's last album, which could be enough to jumpstart her dreams.

I'd just listened to an interview with Dolly Parton when I read this, and so that's the voice that I heard Decklee's sections in (yes, yes, I know that a Tennessee accent is not the same as an Arkansas accent). Decklee is not Dolly Parton, though: she may have faced some of the same barriers—poverty, being a woman in a male-dominated industry in a male-dominated culture, people assuming that a Southern accent means lack of intelligence, people assuming that being blonde means lack of intelligence—but Decklee's stratospheric rise is, by necessity, grasping and calculated. She has the goods—but she needs every advantage to deliver on them.

It keeps Decklee from being an entirely sympathetic character, but that's what I loved most about the book. Darren's story is much more standard YA fare: there's a boy, a minor identity crisis, a journalism dream, some family concerns. Darren is much more easily likeable because we've all been there, one way or another. Decklee, though, raises hard questions about just how much a dream is worth—are there things you would not willingly give up? Is her dream worth it, in the end?

I would have liked to spend more time with Decklee, because there's an extent to which her voice is more distant, less possible to get a full read on. I wouldn't mind a follow-up book about Mickenlee, either—she's far more sympathetic but also less fleshed out, and there is much about her story that remains a mystery in this book. I can hope...

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

*I read an ARC, and quotes may not be final.

Wednesday, April 3, 2024

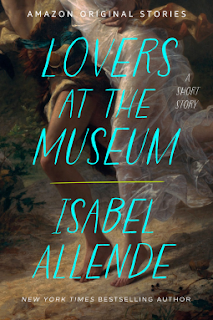

Review: Short story: "Lovers at the Museum" by Isabel Allende

Published April 2024 via Amazon Original Stories

It's been too long since I read any Isabel Allende. In "Lovers at the Museum", a man and a woman are awoken at (you guessed it) a museum. They've clearly been there overnight, but nobody is sure just how—how did they evade the guards, the alarms? They haven't stolen or broken anything, so is there a crime with which to charge them?

Allende is known for her magical realism, and true to form, there are more questions than answers here. We're left to fill in the blanks, to believe or not believe what Bibiña and Indar have to say about what happened the night before. The story drifts along, and not all that much happens, but it doesn't really matter because it's so clear that Allende is in control of the narrative (even if the local police wished otherwise). I suspect that if I had a different cultural context or education, I'd make even more connections here, so I'll be curious to see what other readers make of it.

Either way, a reminder to go update my TBR!

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Tuesday, April 2, 2024

Review: "Fi" by Alexandra Fuller

Published April 2024 via Grove Press

★★★★

All parents who hear of Fi's death have told me this: I wouldn't survive the death of my child, as if my child's death must therefore have been a lesser death than the death of their child would be. Or me, as if I must be a less grief-stricken parent than they would be, if it happened to them. I tell them that I didn't survive and also that I did. Both things happened. (loc. 1358*)

Alexandra Fuller was still grieving the loss of her father when the unthinkable happened—her son Fi died suddenly, unexpectedly, still in the prime of his youth. And Fuller came undone, because what else can you do when that happens?

This is a grief memoir—full stop. Fuller is a hell of a writer, which is not news. Here she spills herself broken onto the page: questioning how she can possibly be expected to survive, pulling from book after book and writer after writer to articulate the depths of her loss and apply balm to her soul. She takes to the mountains and the sky, to the ocean and a grief retreat and a meditation retreat, not in some sort of targeted quest but because the only thing she can do is give her life over to grief, and to find new rhythms for it.

It's worse in town, in the condo, my restlessness, my panic. Only the wild—even the scorched, diminished, smoke-hazed wild—seems conducive to my unwieldy grief. Grand enough to be the grief, to soak up the grief, to reflect it back at me, my feelings as thunder, wind, wildfire. In the mountains, I'd understood the warp and weft of my grief; I'd accepted its weather. In the mountains my grief was shouted back at me with praise and with majesty, in the oldest, most sovereign sense of that word. (loc. 1628)

I have not read Travel Light, Move Fast, Fuller's memoir about her father's death, but Fi died when she was partway through writing it, and there's no way on earth that that didn't reset the shape of that book. Someday I'll pick that up too, because I'm curious about how they overlap and how they don't, and also because I don't think it's possible for Fuller to write a book that is anything other than dramatic and sharp and so vivid it hurts.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

*I read an ARC, and quotes may not be final.

Review: "The Summer I Fell" by Sli Ndhlovu

The Summer I Fell by Sli Ndhlovu Published October 2025 ★★ A brief young adult romance set in South Africa. My library recently started purc...

-

Bloody Mary by Kristina Gehrmann English edition published July 2025 via Andrews McMeel ★★★★ You know the story. A princess is born—but beca...

-

Three Ordinary Girls by Tim Brady Published February 2021 via Citadel Press ★★★ For all that I've heard about the strength of the Dutch ...

-

Elf Zahlen von Lee Child (übersetzt von Kerstin Fricke) Herausgegeben von Amazon Original Stories Ein Job für einen amerikanischen Mathemati...