Nobody in Particular by Sophie Gonzales

Published June 2025 via Wednesday Books

★★★

Normally, Danni and Rosemary wouldn't meet. Danni is talented at music but otherwise an American commoner, nobody in particular, and Rosemary is a literal princess who has, historically, blown off the weight of her position. But in boarding school, they overlap—and they start to find that their circumstantial differences might mean less than they think, and also that staying together might cause insurmountable problems for them both.

Gonzales established herself as a "yes please" kind of author for me with the first book of hers that I read, and since I have a weakness for boarding school stories and princess stories (may these weaknesses never fade), this was not exactly a hard sell for me. It's about what you'd expect: cute and pretty light and with the occasional castle thrown in.

What really interests me, though, is the author's note at the beginning of the book. It's long enough that I won't quote, but Gonzales says that the first draft was written eleven years ago—but that at the time publishers told her, over and over again, that queer royal romance was too niche. This was of course wildly untrue, as many books published since have proven...and it wasn't all that long before Gonzales's draft went from too niche (according to the publishers) to something that had already been done, including with an unnamed, unrelated book that was especially similar.

Obviously we know this background only because both Gonzales and the folks at St. Martin's eventually went forward with publishing this book! But that author's note gave me so much food for thought throughout the book. Because: I am one of those readers who would have found this so valuable (and validating) a decade or more ago, when I was still struggling to find queer books that didn't hinge on violence and homophobia. Part of me is pretty annoyed that publishers didn't think there was a market for this book back then. And...I'm pretty sure I've read that unnamed, unrelated, similar book as well. Actually, I'm pretty sure I reread it—completely coincidentally—a few weeks before reading Nobody in Particular. (I am sometimes very consistent.)

Some parts of this book do feel a bit dated—there's a big to-do about one character coming out, for example, in a way that I associate more with less recent queer lit. (Although obviously coming-out stories are still valid and important, there's something of an arc to the way queer lit has told its stories over time—from queer characters meeting serious violence or being run out of town, to queer characters getting a happy or happy-of-sorts ending but only after lots of homophobia along the way, to extremely angsty coming-out stories, to much more matter-of-fact coming-out stories, and eventually to stories in which the characters are just comfortably queer to begin with and get on with their lives and romances. And then the whole thing started over with stories featuring trans characters...) Would I have been thinking that if I hadn't read the author's note, though, and also every piece of queer lit I could get my hands on in my teens and early twenties—perhaps not! I think I was both the right and the wrong reader for this: right, because (again) of that weakness for boarding school stories and princess stories and also Gonzales's books in general; wrong, because I do sometimes have such weird and specific tastes and because I know how much Gonzales has evolved as a writer in the past decade (as in: I know, because I have read her more recent books) and part of me wishes—unfairly!—that I could see what she might have done with this story today.

All of which is to say: if you're looking for a boarding school story, or a princess story, and want a fairly light, quick read, this is one for you! Rosemary and Danni can be absolute dummies at times, but that is not criticism; that is the state of teenagers and also YA lit in general. This isn't the most realistic of stories, but that's sort of the point; it's pure escapism at times, so buckle up and put on your plastic crowns and settle in for some princess fantasies.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Friday, May 30, 2025

Thursday, May 29, 2025

Review: "So Gay for You" by Leisha Hailey and Kate Moennig

So Gay for You by Leisha Hailey and Kate Moennig

Published June 2025 via St. Martin's

★★★★

Back in the early 2000s, Leisha Hailey and Kate Moennig—unknowns trying to break into Hollywood—both showed up for an audition. They clicked. Moennig got the part...but the writers worked Hailey into the show as well, and a friendship—to say nothing of a hella memorable show—was born.

Every day, between 8:30 and 9:00 a.m., one of us calls the other for a morning check-in. Like clockwork, my wife[...] will hand me the phone and say, without a hint of resentment, not even looking up from her New York Times, "It's your other wife." (loc. 3083*)

I watched maybe two seasons of The L Word at the time (rather behind release schedule, I imagine). This was back when, if you wanted to watch something you didn't otherwise have access to, someone who understood the Internet better than I did burned you a DVD. (I'm neither justifying this nor recommending it, but my family did not have television, it was the early 2000s in a red state, and teenaged me would literally not have known where to find this show through more above-board means.) Even as a teenager who had watched precious little television, I knew it was not good television, and yet: how could you look away? Teenaged me had scoured Alison Bechdel's Fun Home to make a list of every queer book she mentioned and take that list to the library. I found maybe two of the books on the list, and at least one of those books was wildly depressing. Books that celebrated queerness were hard to find and shows even harder to find (even if you had television). And here were Moennig and Hailey and the rest of the cast presenting queerness as something that was just there, (mostly) not as coming-out stories or trauma but as romance and drama and found family. And two decades later—without, let's be honest, any intention of ever going back and watching the rest of the show**—I'm still here for it.

So this is absolutely a book for readers for whom The L Word meant something or means something. It's a look beyond the ripped DVD at what it was like to make the show and with it redefine part of queer culture. Hailey and Moennig write through a lot of the plot points of the show, and you don't need to be intimately familiar with the show to follow it (again: I've seen maybe two seasons, twenty years ago); I'd still recommend the book to other curious readers and particularly to baby queers who are too young to have caught the first L Word wave. But at its core...this is a love letter to a time and place and context and found family.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

**Nothing personal, L Word, I just still don't watch TV

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published June 2025 via St. Martin's

★★★★

Back in the early 2000s, Leisha Hailey and Kate Moennig—unknowns trying to break into Hollywood—both showed up for an audition. They clicked. Moennig got the part...but the writers worked Hailey into the show as well, and a friendship—to say nothing of a hella memorable show—was born.

Every day, between 8:30 and 9:00 a.m., one of us calls the other for a morning check-in. Like clockwork, my wife[...] will hand me the phone and say, without a hint of resentment, not even looking up from her New York Times, "It's your other wife." (loc. 3083*)

I watched maybe two seasons of The L Word at the time (rather behind release schedule, I imagine). This was back when, if you wanted to watch something you didn't otherwise have access to, someone who understood the Internet better than I did burned you a DVD. (I'm neither justifying this nor recommending it, but my family did not have television, it was the early 2000s in a red state, and teenaged me would literally not have known where to find this show through more above-board means.) Even as a teenager who had watched precious little television, I knew it was not good television, and yet: how could you look away? Teenaged me had scoured Alison Bechdel's Fun Home to make a list of every queer book she mentioned and take that list to the library. I found maybe two of the books on the list, and at least one of those books was wildly depressing. Books that celebrated queerness were hard to find and shows even harder to find (even if you had television). And here were Moennig and Hailey and the rest of the cast presenting queerness as something that was just there, (mostly) not as coming-out stories or trauma but as romance and drama and found family. And two decades later—without, let's be honest, any intention of ever going back and watching the rest of the show**—I'm still here for it.

So this is absolutely a book for readers for whom The L Word meant something or means something. It's a look beyond the ripped DVD at what it was like to make the show and with it redefine part of queer culture. Hailey and Moennig write through a lot of the plot points of the show, and you don't need to be intimately familiar with the show to follow it (again: I've seen maybe two seasons, twenty years ago); I'd still recommend the book to other curious readers and particularly to baby queers who are too young to have caught the first L Word wave. But at its core...this is a love letter to a time and place and context and found family.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

**Nothing personal, L Word, I just still don't watch TV

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Tuesday, May 27, 2025

Review: "When It All Burns" by Jordan Thomas

When It All Burns by Jordan Thomas

Published May 2025 via Riverhead Books

★★★★

By some measures, being a hotshot is among the most difficult jobs on earth. Hotshots don't just mountaineer; they mountaineer with chainsaws, and they do so in thick smoke, often in unprecedented heat, along the edges of the most extreme conflagrations in recorded history. In the mountains of California's Sierra Nevada range, hotshots sometimes train alongside Olympic athletes because their jobs require an equivalent level of tactical athleticism. They need to be able to hike for hours, cut line for miles, command helicopters and airplanes from their radios on the ground, and maintain a constant awareness of all the shifting conditions that could change the fire's spread. Their lives depend on these abilities. (loc. 364*)

In another life, I want to be a wildland firefighter. Not necessarily a hotshot or a smokejumper, and not this life—not when I'm busy doing other things and my knees are already too old to cooperate with me much of the time and I already know far too much about how little the US government thinks of the people doing this difficult, often precise, dangerous work. (Maybe in other countries it is better—quick, where are the wildland firefighting memoirs from Europe, Asia, Oceania?) But Thomas was a wildland firefighter, in this lifetime. A hotshot and also an academic, he was studying anthropology when he got interested in fire—fire, and firefighting, and the ways Native Americans used fire to manage the land, and the ways the colonizers weaponized that fire by criminalizing it, positioning nature as an adversary, creating conditions in which more and more flammable material built up, and humans could manage it less and less.

Thomas blends memoir with research here. The memoir part describes his season on a hotshot crew in one of the hottest years on record, one in which he and the rest of the crew battled blazes that would have been unimaginable to all but tuned-in scientists even fifty years ago. Thomas was the new guy on the crew—not new to wildland firefighting but new to being a hotshot (highly trained, the technicians of wildland firefighting), and struggling to learn his role as a sawyer and keep up and simply conceive of the scale of what they were doing. The research part of things digs deep into history and anthropology, from massacres of Native Americans to the continued devastation inflicted by loggers and politicians.

It's a hard read but a gripping one. I've read a lot of firefighting memoir (again: in another life...), so I was already familiar with a lot of the wtf moments (did you know that wildland firefighters are typically seasonal employees working on low pay and no benefits—meaning, crucially, no insurance if they're injured on the job? I did, but it makes me mad every time I read about it), but there's always something new to learn (did you know that a lot of fire retardant dumps are done—at great expense—to quell public outcry of "where are the planes?" rather than because it will actually be useful where it is being dumped? I did not!).

I've you've been thinking at all about fires and climate change recently, or fires and history, or climate change and history, this is a good one—one of the better books about fire that I've read. It slows down a little at the end (as expected, Thomas did not pursue a longer career as a hotshot), but it's full of fascinating, if often depressing, context and detail.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Published May 2025 via Riverhead Books

★★★★

By some measures, being a hotshot is among the most difficult jobs on earth. Hotshots don't just mountaineer; they mountaineer with chainsaws, and they do so in thick smoke, often in unprecedented heat, along the edges of the most extreme conflagrations in recorded history. In the mountains of California's Sierra Nevada range, hotshots sometimes train alongside Olympic athletes because their jobs require an equivalent level of tactical athleticism. They need to be able to hike for hours, cut line for miles, command helicopters and airplanes from their radios on the ground, and maintain a constant awareness of all the shifting conditions that could change the fire's spread. Their lives depend on these abilities. (loc. 364*)

In another life, I want to be a wildland firefighter. Not necessarily a hotshot or a smokejumper, and not this life—not when I'm busy doing other things and my knees are already too old to cooperate with me much of the time and I already know far too much about how little the US government thinks of the people doing this difficult, often precise, dangerous work. (Maybe in other countries it is better—quick, where are the wildland firefighting memoirs from Europe, Asia, Oceania?) But Thomas was a wildland firefighter, in this lifetime. A hotshot and also an academic, he was studying anthropology when he got interested in fire—fire, and firefighting, and the ways Native Americans used fire to manage the land, and the ways the colonizers weaponized that fire by criminalizing it, positioning nature as an adversary, creating conditions in which more and more flammable material built up, and humans could manage it less and less.

Thomas blends memoir with research here. The memoir part describes his season on a hotshot crew in one of the hottest years on record, one in which he and the rest of the crew battled blazes that would have been unimaginable to all but tuned-in scientists even fifty years ago. Thomas was the new guy on the crew—not new to wildland firefighting but new to being a hotshot (highly trained, the technicians of wildland firefighting), and struggling to learn his role as a sawyer and keep up and simply conceive of the scale of what they were doing. The research part of things digs deep into history and anthropology, from massacres of Native Americans to the continued devastation inflicted by loggers and politicians.

It's a hard read but a gripping one. I've read a lot of firefighting memoir (again: in another life...), so I was already familiar with a lot of the wtf moments (did you know that wildland firefighters are typically seasonal employees working on low pay and no benefits—meaning, crucially, no insurance if they're injured on the job? I did, but it makes me mad every time I read about it), but there's always something new to learn (did you know that a lot of fire retardant dumps are done—at great expense—to quell public outcry of "where are the planes?" rather than because it will actually be useful where it is being dumped? I did not!).

I've you've been thinking at all about fires and climate change recently, or fires and history, or climate change and history, this is a good one—one of the better books about fire that I've read. It slows down a little at the end (as expected, Thomas did not pursue a longer career as a hotshot), but it's full of fascinating, if often depressing, context and detail.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Monday, May 26, 2025

Review: "Disappoint Me" by Nicola Dinan

Disappoint Me by Nicola Dinan

Published May 2025 via The Dial Press

★★★★

A tumble down the stairs convinces Max that it's time for a change: time for a stable relationship; time to settle down; time, perhaps, for a bit of heteronormativity. Enter Vincent.

On paper—and in person—Vincent seems like the perfect fit. Attractive, good job, good listener; he's Chinese enough to make Max's mother happy and unfazed by Max being trans. But behind all that there's something else: there's who Vincent was when he was younger, and the choices he made then. And these are neither things he wants Max to know about nor things he can hide forever.

I decide not to say anything, buckling under the pressure to upgrade by palatability. (loc. 758*)

The book weaves back and forth between then and now: now, from Max's perspective, starting to build this new life with Vincent; and then, from Vincent's perspective, when Vincent is young and stupid and backpacking through Asia. In places I found the book slow going just because Max's side of things is so much easier to take—Max is no saint, but she has her head basically screwed on right, and she has (usually) a strong sense of right and wrong. Vincent was harder to handle; young-and-dumb-tourist is not one of my favourite character types (though it's in here for a reason), and I could feel the Bad coming well before I had a sense of what shape it would take.

Max—and by extension the reader—is asked, then, to decide: what transgressions can be forgiven, and by whom? That is: even if Max decides that she can look past the things Vincent did in his youth, what right does she have to forgive? How do they move forward? And (largely unasked, in the book) is there an element of atonement in Vincent's relationship with Max?

I love how messy things get, if not the things themselves—I don't like my characters squeaky-clean and perfect, because shades of grey make for more realistic and more interesting reading. It helps that Vincent's transgressions are not the worst of the book, but also that there are other characters (e.g., Simone) operating in shades of grey, or rather doing both good things and bad. Max does have to make decisions about the relationship, and what to do with it, as the book nears its end, and I had mixed feelings about the way things pan out. There are a limited number of ways the book could go there (the relationship could end; the relationship could continue; the book could end without the reader finding out what happens). I suspect that I was never going to be entirely satisfied with any of those options, which is actually a good thing in terms of the book—again, grey area. It'll be interesting to see where Dinan goes next.

Thanks to the author and publisher for inviting me to read a review copy through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Published May 2025 via The Dial Press

★★★★

A tumble down the stairs convinces Max that it's time for a change: time for a stable relationship; time to settle down; time, perhaps, for a bit of heteronormativity. Enter Vincent.

On paper—and in person—Vincent seems like the perfect fit. Attractive, good job, good listener; he's Chinese enough to make Max's mother happy and unfazed by Max being trans. But behind all that there's something else: there's who Vincent was when he was younger, and the choices he made then. And these are neither things he wants Max to know about nor things he can hide forever.

I decide not to say anything, buckling under the pressure to upgrade by palatability. (loc. 758*)

The book weaves back and forth between then and now: now, from Max's perspective, starting to build this new life with Vincent; and then, from Vincent's perspective, when Vincent is young and stupid and backpacking through Asia. In places I found the book slow going just because Max's side of things is so much easier to take—Max is no saint, but she has her head basically screwed on right, and she has (usually) a strong sense of right and wrong. Vincent was harder to handle; young-and-dumb-tourist is not one of my favourite character types (though it's in here for a reason), and I could feel the Bad coming well before I had a sense of what shape it would take.

Max—and by extension the reader—is asked, then, to decide: what transgressions can be forgiven, and by whom? That is: even if Max decides that she can look past the things Vincent did in his youth, what right does she have to forgive? How do they move forward? And (largely unasked, in the book) is there an element of atonement in Vincent's relationship with Max?

I love how messy things get, if not the things themselves—I don't like my characters squeaky-clean and perfect, because shades of grey make for more realistic and more interesting reading. It helps that Vincent's transgressions are not the worst of the book, but also that there are other characters (e.g., Simone) operating in shades of grey, or rather doing both good things and bad. Max does have to make decisions about the relationship, and what to do with it, as the book nears its end, and I had mixed feelings about the way things pan out. There are a limited number of ways the book could go there (the relationship could end; the relationship could continue; the book could end without the reader finding out what happens). I suspect that I was never going to be entirely satisfied with any of those options, which is actually a good thing in terms of the book—again, grey area. It'll be interesting to see where Dinan goes next.

Thanks to the author and publisher for inviting me to read a review copy through NetGalley.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Saturday, May 24, 2025

Review: "Come as You Are" by Dahlia Adler

Come as You Are by Dahlia Adler

Published May 2025 via Wednesday Books

★★★★

You know the story: Girl tries to escape complications at home and have a nice normal boring existence at boarding school. Girl might succeed...except girl is placed in boys' dorm by accident. Shenanigans ensue, and girl decides that if she cannot have a non-reputation, she might as well have a Reputation of her own making.

First things first, then second things second, then third things and a caveat third.

First things first: Adler writes both f/f and f/m romance (and possibly other things, but I haven't read her entire backlist), and while there's plenty of queer coding in this book, that dark-haired character on the cover is (alas) not a butch lesbian. If that disappoints you, there's a solution! Read this anyway, and tell the publisher how much you want to see a queer sequel...because there's definitely sufficient setup for that.* And that's all I'll say on that particular subject.

Second things second: I've loved all of Adler's books that I've read, and this was no exception. I giggled out loud (and then had to explain myself to my partner) more than once, and that doesn't happen often. I enjoy how ready Evie is to come out swinging—she has a great poker face, which makes sense given some of her plot points. And her repartee with Salem and Sabrina in particular is just aces. I wasn't sure what kind of pairing to expect going in (I did not get past "boarding school" in the description before I chucked the book on my to-read list; that was almost a year before I read the book, and I didn't reread the description in the meantime—I knew it would be good read regardless, and I like to be surprised), so I spent a big chunk of the book expecting Evie to end up with a different pairing, and it turns out that reading YA romance is way more fun when it's not immediately glaringly obvious who the love interest is. (I mean...it is. If you've bothered to read the description. But if you're going in blind, it's fun.) I also love that one of the people Evie meets early on, whom she expects to be a tool to end all tools, ends up to be a pretty okay guy, if a total dudebro. Be prepared to hear a loooot about teenagers getting it on, but it's a fun read.

Third things third: This is where the caveat comes in. If you've ever been to boarding school, Come as You Are requires, ah...a fair amount of suspension of disbelief. (Is not, has never been, probably never will be my forte.) It's like this: I went to boarding school. Granted, mine was free,** public** nerd school in the South,*** not a fancy, expensive prep school in New England; also, I am an expert on neither my boarding school nor boarding schools in general. However...I do know that my school sometimes ended up with more students than they'd bargained for. And I know some of the ways they dealt with that: They turned singles into doubles. They turned doubles into triples. They turned triples into quads. They turned storage closets into singles. (Literally, there were windowless rooms in one of the boys' dorms known as closet singles and elevator singles, and to the best of my knowledge the former were originally closets and the latter were originally part of an elevator shaft. Was this legal? Who knows. But it was a thing.) One year, they chucked some beds and desks into the lounge of a girls' dorm and called it a bedroom until enough girls in real dorm rooms dropped out (a few people every year got homesick or couldn't hack it academically...and in the boys' dorms, one or two boys typically did something really, really dumb and got expelled early on) and the girls in the lounge could move elsewhere.

What they definitely never did: moved a girl into a boys' dorm. What they definitely, definitely never did: moved a girl into a boys' dorm without extensive conversations with the girl's parents, and lots of waivers signed (probably by everybody's parents), and about a thousand extra rules for the girl. (There probably would have been a lot fewer rules for the boys, let's be real. This was the South.) With no effort at any point in time to move her to a girls' dorm. And in the 0.0000001% chance that that would somehow happen, there is a further 0% chance that the girl would decide to respond by never locking her door, because what? Boys in boys' dorms are awful. The stories Evie comes out with (like boys playing a game involving shouting "penis" at increasing volumes) are nothing compared to the stories I heard from the boys' dorms at my school. (Just...trust me on this one. Those are not stories that I'm repeating on the Internet.) Oh, and girls in girls' dorms can be a different kind of awful, but that's a whole 'nother thing. As is the part where there are at least a dozen characters in this book who would have been expelled from my high school, post-haste, for any number of reasons, and I swear to the giant spaghetti monster in the sky that my school was not especially strict—they were just worried about things like student safety, and also their reputation and being sued.

Now...I have to assume that Adler knows all this, and she chose to run with it anyway, because you cannot be smart enough to write books this good and also fool enough to think that, you know, Evie's experience would be what Evie's experience is. So I'm taking that as what it is, but also, well. Writing a dissertation on the ways that boarding schools would be more likely to react. Because I'm not very good at suspension of disbelief.

So go forth and read anyway, and know that if you someday send a kid off to boarding school, none of the things in this book will happen, but much worse things probably will.**** And then please hassle Wednesday Books (politely) for that sequel.

* Hey Wednesday Books—and Dahlia Adler—I'd love a queer sequel!

** Yes, really (x2).

*** It was...an experience.

**** Kidding. Or am I?

Thanks to the author and publisher for inviting me to read a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via Wednesday Books

★★★★

You know the story: Girl tries to escape complications at home and have a nice normal boring existence at boarding school. Girl might succeed...except girl is placed in boys' dorm by accident. Shenanigans ensue, and girl decides that if she cannot have a non-reputation, she might as well have a Reputation of her own making.

First things first, then second things second, then third things and a caveat third.

First things first: Adler writes both f/f and f/m romance (and possibly other things, but I haven't read her entire backlist), and while there's plenty of queer coding in this book, that dark-haired character on the cover is (alas) not a butch lesbian. If that disappoints you, there's a solution! Read this anyway, and tell the publisher how much you want to see a queer sequel...because there's definitely sufficient setup for that.* And that's all I'll say on that particular subject.

Second things second: I've loved all of Adler's books that I've read, and this was no exception. I giggled out loud (and then had to explain myself to my partner) more than once, and that doesn't happen often. I enjoy how ready Evie is to come out swinging—she has a great poker face, which makes sense given some of her plot points. And her repartee with Salem and Sabrina in particular is just aces. I wasn't sure what kind of pairing to expect going in (I did not get past "boarding school" in the description before I chucked the book on my to-read list; that was almost a year before I read the book, and I didn't reread the description in the meantime—I knew it would be good read regardless, and I like to be surprised), so I spent a big chunk of the book expecting Evie to end up with a different pairing, and it turns out that reading YA romance is way more fun when it's not immediately glaringly obvious who the love interest is. (I mean...it is. If you've bothered to read the description. But if you're going in blind, it's fun.) I also love that one of the people Evie meets early on, whom she expects to be a tool to end all tools, ends up to be a pretty okay guy, if a total dudebro. Be prepared to hear a loooot about teenagers getting it on, but it's a fun read.

Third things third: This is where the caveat comes in. If you've ever been to boarding school, Come as You Are requires, ah...a fair amount of suspension of disbelief. (Is not, has never been, probably never will be my forte.) It's like this: I went to boarding school. Granted, mine was free,** public** nerd school in the South,*** not a fancy, expensive prep school in New England; also, I am an expert on neither my boarding school nor boarding schools in general. However...I do know that my school sometimes ended up with more students than they'd bargained for. And I know some of the ways they dealt with that: They turned singles into doubles. They turned doubles into triples. They turned triples into quads. They turned storage closets into singles. (Literally, there were windowless rooms in one of the boys' dorms known as closet singles and elevator singles, and to the best of my knowledge the former were originally closets and the latter were originally part of an elevator shaft. Was this legal? Who knows. But it was a thing.) One year, they chucked some beds and desks into the lounge of a girls' dorm and called it a bedroom until enough girls in real dorm rooms dropped out (a few people every year got homesick or couldn't hack it academically...and in the boys' dorms, one or two boys typically did something really, really dumb and got expelled early on) and the girls in the lounge could move elsewhere.

What they definitely never did: moved a girl into a boys' dorm. What they definitely, definitely never did: moved a girl into a boys' dorm without extensive conversations with the girl's parents, and lots of waivers signed (probably by everybody's parents), and about a thousand extra rules for the girl. (There probably would have been a lot fewer rules for the boys, let's be real. This was the South.) With no effort at any point in time to move her to a girls' dorm. And in the 0.0000001% chance that that would somehow happen, there is a further 0% chance that the girl would decide to respond by never locking her door, because what? Boys in boys' dorms are awful. The stories Evie comes out with (like boys playing a game involving shouting "penis" at increasing volumes) are nothing compared to the stories I heard from the boys' dorms at my school. (Just...trust me on this one. Those are not stories that I'm repeating on the Internet.) Oh, and girls in girls' dorms can be a different kind of awful, but that's a whole 'nother thing. As is the part where there are at least a dozen characters in this book who would have been expelled from my high school, post-haste, for any number of reasons, and I swear to the giant spaghetti monster in the sky that my school was not especially strict—they were just worried about things like student safety, and also their reputation and being sued.

Now...I have to assume that Adler knows all this, and she chose to run with it anyway, because you cannot be smart enough to write books this good and also fool enough to think that, you know, Evie's experience would be what Evie's experience is. So I'm taking that as what it is, but also, well. Writing a dissertation on the ways that boarding schools would be more likely to react. Because I'm not very good at suspension of disbelief.

So go forth and read anyway, and know that if you someday send a kid off to boarding school, none of the things in this book will happen, but much worse things probably will.**** And then please hassle Wednesday Books (politely) for that sequel.

* Hey Wednesday Books—and Dahlia Adler—I'd love a queer sequel!

** Yes, really (x2).

*** It was...an experience.

**** Kidding. Or am I?

Thanks to the author and publisher for inviting me to read a review copy through NetGalley.

Thursday, May 22, 2025

Review: "Flirty Dancing" by Jennifer Moffatt

Flirty Dancing by Jennifer Moffatt

Published May 2025 via St. Martin's Griffin

★★★★

Archer is living his dream—sort of. A few months ago, he gave up his dreary desk job to pursue a career in dance. But he's struck out time and time again, and he's perilously close to having to return to Ohio and to one of those dreary desk jobs. When saving grace comes, it's in an unexpected form: a queer resort in the Catskills. And his once-upon-a-time crush happens to be working there too...

"Well, stop standing there like you carried a watermelon. Grab a beer," Betty said, nodding at the fridge. (loc. 329*)

If I'm honest, I read this for the Dirty Dancing retelling. Luckily, this is one of those retellings that is smart about it (I'm a broken record on this, but what can you do)—rather than a straight (pun intended) retelling, Flirty Dancing is inspired by Dirty Dancing but deviates as necessary to make for a better story. (After all, cultural context doesn't always translate; both the 60s, when DD is set, and the 80s, when it was written, are a long way off from the 2020s.) Archer is, loosely, the Baby of the story, but he's an employee rather than a resort guest, and when Mateo (the Johnny of the book) scorns Archer's naïveté, it's not because he thinks Archer is talentless or incompetent, but just that he is, well, sometimes a little naïve.

Overall, this makes for a cute, entertaining read. Mateo has some baggage to sort through, and Archer spends much of the book in need of a confidence boost, but the cast of characters is lively, and even the people who turn out to have...fewer scruples than others...are allowed to have some complexity rather than being written off as bad apples.

This doesn't outshine Dirty Dancing, but it's a solid twist on a much-loved story. It'll be interesting to see what Moffatt does next.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via St. Martin's Griffin

★★★★

Archer is living his dream—sort of. A few months ago, he gave up his dreary desk job to pursue a career in dance. But he's struck out time and time again, and he's perilously close to having to return to Ohio and to one of those dreary desk jobs. When saving grace comes, it's in an unexpected form: a queer resort in the Catskills. And his once-upon-a-time crush happens to be working there too...

"Well, stop standing there like you carried a watermelon. Grab a beer," Betty said, nodding at the fridge. (loc. 329*)

If I'm honest, I read this for the Dirty Dancing retelling. Luckily, this is one of those retellings that is smart about it (I'm a broken record on this, but what can you do)—rather than a straight (pun intended) retelling, Flirty Dancing is inspired by Dirty Dancing but deviates as necessary to make for a better story. (After all, cultural context doesn't always translate; both the 60s, when DD is set, and the 80s, when it was written, are a long way off from the 2020s.) Archer is, loosely, the Baby of the story, but he's an employee rather than a resort guest, and when Mateo (the Johnny of the book) scorns Archer's naïveté, it's not because he thinks Archer is talentless or incompetent, but just that he is, well, sometimes a little naïve.

Overall, this makes for a cute, entertaining read. Mateo has some baggage to sort through, and Archer spends much of the book in need of a confidence boost, but the cast of characters is lively, and even the people who turn out to have...fewer scruples than others...are allowed to have some complexity rather than being written off as bad apples.

This doesn't outshine Dirty Dancing, but it's a solid twist on a much-loved story. It'll be interesting to see what Moffatt does next.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Review: "Spent" by Alison Bechdel

Spent by Alison Bechdel

Published May 2025 via Mariner Books

★★★★★

Oh gosh. Okay, backstory: Bechdel's comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For was syndicated in my sister's college newspaper, which was how my sister found out about it. She brought one of the collections home with her one holiday and left it on the kitchen table. I read it—my mother read it—my father read it—my father went upstairs to the computer and ordered every other volume that was out at the time. When Fun Home came out, my mother ordered about six copies to send to various relatives (and the reason I own a copy of The Secret to Superhuman Strength is that my mother shipped that to me); now she has multiple copies of Spent on order, too, for the same reason. (My family, we are fans. Also, my husband and I talked Bechdel on our first date, which is maybe less specific than it might be when you consider that he's a comic artist and I...well, I just read a lot.)

Anyway, all of this is to say: This is a book unlike any of Bechdel's previous books. To be perfectly honest, if you've read both DTWOF and Bechdel's memoirs, I'd recommend skipping all of the reviews—and skipping the book description—and diving right in so that you can be gloriously confused and delighted. I read the description* when I first saw this book, but I have a habit of reading a description, shelving a book for future reference, and then forgetting everything but general theme until I pick the book up again; in this case, that meant that I spent a while going "wait, what?" and checking Wikipedia to make sure I hadn't missed something major before figuring it out and settling in to enjoy. And folks, that is a reading experience that I highly recommend.

This is fully enjoyable for readers who have read some but not all of Bechdel's work; certainly it helps if you've read Fun Home (or should I say Death & Taxidermy?), but you don't need to have read it, and you don't need to have read DTWOF. (I'd have to do some rereading to say whether there are specific callbacks to Bechdel's other books.) But—I do think the ideal audience here are those who have read and loved both. This is a catch-up with old friends (if the sort of catch-up where you maybe learn a little too much about them), and it was both so nostalgic and so current.

Plus, that picture of Bechdel near the beginning, where she's wearing gardening boots and scrolling on her phone? That inexplicably looks both 1) exactly as Bechdel generally draws herself and 2) exactly like my mother, who looks 2a) really nothing like Bechdel. And that may be weird and specific and not useful in terms of a book review, but for me it was just an excellent start to the book.

*Maybe. Or maybe I just saw the author and cover and winged the book onto my Goodreads shelf without needing to know more. Who can say?

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via Mariner Books

★★★★★

Oh gosh. Okay, backstory: Bechdel's comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For was syndicated in my sister's college newspaper, which was how my sister found out about it. She brought one of the collections home with her one holiday and left it on the kitchen table. I read it—my mother read it—my father read it—my father went upstairs to the computer and ordered every other volume that was out at the time. When Fun Home came out, my mother ordered about six copies to send to various relatives (and the reason I own a copy of The Secret to Superhuman Strength is that my mother shipped that to me); now she has multiple copies of Spent on order, too, for the same reason. (My family, we are fans. Also, my husband and I talked Bechdel on our first date, which is maybe less specific than it might be when you consider that he's a comic artist and I...well, I just read a lot.)

Anyway, all of this is to say: This is a book unlike any of Bechdel's previous books. To be perfectly honest, if you've read both DTWOF and Bechdel's memoirs, I'd recommend skipping all of the reviews—and skipping the book description—and diving right in so that you can be gloriously confused and delighted. I read the description* when I first saw this book, but I have a habit of reading a description, shelving a book for future reference, and then forgetting everything but general theme until I pick the book up again; in this case, that meant that I spent a while going "wait, what?" and checking Wikipedia to make sure I hadn't missed something major before figuring it out and settling in to enjoy. And folks, that is a reading experience that I highly recommend.

This is fully enjoyable for readers who have read some but not all of Bechdel's work; certainly it helps if you've read Fun Home (or should I say Death & Taxidermy?), but you don't need to have read it, and you don't need to have read DTWOF. (I'd have to do some rereading to say whether there are specific callbacks to Bechdel's other books.) But—I do think the ideal audience here are those who have read and loved both. This is a catch-up with old friends (if the sort of catch-up where you maybe learn a little too much about them), and it was both so nostalgic and so current.

Plus, that picture of Bechdel near the beginning, where she's wearing gardening boots and scrolling on her phone? That inexplicably looks both 1) exactly as Bechdel generally draws herself and 2) exactly like my mother, who looks 2a) really nothing like Bechdel. And that may be weird and specific and not useful in terms of a book review, but for me it was just an excellent start to the book.

*Maybe. Or maybe I just saw the author and cover and winged the book onto my Goodreads shelf without needing to know more. Who can say?

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Sunday, May 18, 2025

Review: "My Beautiful Sisters" by Khalida Popal

My Beautiful Sisters by Khalida Popal

Published May 2025 via Citadel Press

★★★★

In 2021, the US withdrew forces from Afghanistan. The Taliban immediately seized control—and Popal, who was by then living outside the country, immediately began receiving text messages, phone calls, voice notes. She'd once been the most visible face of women's soccer in Afghanistan, and now her former teammates—and the next generation of players—knew that the Taliban would be closing in on them too. They were desperate to get out.

As I started reading this, I remember thinking that it would be purely a story of Popal's attempts to help get these girls and women out of the country before doing so became impossible, perhaps with a bit of her own story sprinkled in; I thought "I wish she'd also written a book about her own experience". But then I kept reading—and this is Popal's story, and it's both devastating and damning.

Growing up in Afghanistan and (during the Taliban's earlier takeover) Pakistan, Popal had it better than many girls of her generation: her parents valued education and independence. They encouraged Popal to speak her mind; they were happy for her to play soccer and develop her leadership skills and push boundaries over and over again. They had their limits, but those limits were based on what they knew of the danger of society rather than on what they thought Popal should be allowed to do.

But better is not easy. Popal describes a world in which if men scaled the walls behind which girls played—walls supposedly there to protect them—and those men hurled abuse at the girls, the girls would be in the wrong. A world in which the girls could trust nobody, not even each other, because there were no mechanisms in place that actually protected them, and anyone who stepped outside the boundaries of convention in even the smallest of ways was assumed to be a deviant in every other way possible—and thus not worthy of protection in the first place.

The strides Popal made with women's soccer when she was in Afghanistan, despite all the barriers she came up against over and over, are incredible, but even then she knew they wouldn't be allowed to last. I said this book was damning, and I meant it: she calls out policies that meant that American soldiers in Afghanistan could shoot to kill when anything threatened them, even if that "threat" was simply an unarmed girl taking a photo with her phone; she notes that FIFA could take a stance by simply not allowing the Afghanistan men's team to play internationally if there is no corresponding women's team—and funding and support for that women's team—and FIFA has chosen instead to bury its head in the sand. And: refugee processing centers that did not understand that just because women had rights in one country did not mean that they were afforded those same rights in their home country, or that a lack of documentation could be a result of having to flee and flee again, or of that same documentation (e.g., proof of playing on a women's soccer team) posing a mortal danger back home.

There's so much frustration here, but Popal is clear-eyed—she knows how multifaceted the problem is, and how short attention spans are. Another crisis occurs, and the world's attention shifts. She's really good about bringing in her teammates' stories and realities while maintaining their privacy; even when individuals have gotten out of the country, their family might remain, and remain in danger. There's hope in here, but there are limits to the happy endings; go in with your eyes wide open.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via Citadel Press

★★★★

In 2021, the US withdrew forces from Afghanistan. The Taliban immediately seized control—and Popal, who was by then living outside the country, immediately began receiving text messages, phone calls, voice notes. She'd once been the most visible face of women's soccer in Afghanistan, and now her former teammates—and the next generation of players—knew that the Taliban would be closing in on them too. They were desperate to get out.

As I started reading this, I remember thinking that it would be purely a story of Popal's attempts to help get these girls and women out of the country before doing so became impossible, perhaps with a bit of her own story sprinkled in; I thought "I wish she'd also written a book about her own experience". But then I kept reading—and this is Popal's story, and it's both devastating and damning.

Growing up in Afghanistan and (during the Taliban's earlier takeover) Pakistan, Popal had it better than many girls of her generation: her parents valued education and independence. They encouraged Popal to speak her mind; they were happy for her to play soccer and develop her leadership skills and push boundaries over and over again. They had their limits, but those limits were based on what they knew of the danger of society rather than on what they thought Popal should be allowed to do.

But better is not easy. Popal describes a world in which if men scaled the walls behind which girls played—walls supposedly there to protect them—and those men hurled abuse at the girls, the girls would be in the wrong. A world in which the girls could trust nobody, not even each other, because there were no mechanisms in place that actually protected them, and anyone who stepped outside the boundaries of convention in even the smallest of ways was assumed to be a deviant in every other way possible—and thus not worthy of protection in the first place.

The strides Popal made with women's soccer when she was in Afghanistan, despite all the barriers she came up against over and over, are incredible, but even then she knew they wouldn't be allowed to last. I said this book was damning, and I meant it: she calls out policies that meant that American soldiers in Afghanistan could shoot to kill when anything threatened them, even if that "threat" was simply an unarmed girl taking a photo with her phone; she notes that FIFA could take a stance by simply not allowing the Afghanistan men's team to play internationally if there is no corresponding women's team—and funding and support for that women's team—and FIFA has chosen instead to bury its head in the sand. And: refugee processing centers that did not understand that just because women had rights in one country did not mean that they were afforded those same rights in their home country, or that a lack of documentation could be a result of having to flee and flee again, or of that same documentation (e.g., proof of playing on a women's soccer team) posing a mortal danger back home.

There's so much frustration here, but Popal is clear-eyed—she knows how multifaceted the problem is, and how short attention spans are. Another crisis occurs, and the world's attention shifts. She's really good about bringing in her teammates' stories and realities while maintaining their privacy; even when individuals have gotten out of the country, their family might remain, and remain in danger. There's hope in here, but there are limits to the happy endings; go in with your eyes wide open.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Friday, May 16, 2025

Review: "The Nightmare Before Kissmas" by Sara Raasch

The Nightmare Before Kissmas by Sara Raasch

Published October 2024 via Bramble

★★★

When Christmas meets Halloween...

I picked this up thinking it was YA, and to be perfectly honest it wasn't until I'd finished the book and read a brief interview with the author that I realised it was marketed as a romance novel. It's spicier than your average YA book, but then lines have gotten more and more blurred between YA and NA and adults romance, so... With Coal and Hex in college, this is largely a coming-of-age story; Coal has to figure out how to grow up and distinguish himself from his father (or rather, from Father Christmas), and, well...I think I'm going to carry on mentally treating this as YA.

At any rate, it's a basically cute story. The Red, White & Royal Blue comparison is bollocks, of course, but I guess when a book (an excellent book!) gets that much press, everyone wants it as a comp title. I think I'd have liked a bit more worldbuilding, and in particular an acknowledgement of non-Western holidays—Father Winter this book's Santa talks about expanding Christmas's global reach, but (perhaps to keep him from looking irredeemably bad-guy?) nobody ever explicitly mentions that that probably means he wants to have Christmas overrun things like Eid and Holi. The optics would not be great, would they? Except...I think that's exactly what he's trying to do. Would have liked to see that discussed a bit more directly, because it could have added quite a bit of depth and I'd be side-eyeing the concept less now.

I won't go out of my way to read the next book, but if a future book in the series brings in some holidays I know less about, I'd consider jumping back in.

Published October 2024 via Bramble

★★★

When Christmas meets Halloween...

I picked this up thinking it was YA, and to be perfectly honest it wasn't until I'd finished the book and read a brief interview with the author that I realised it was marketed as a romance novel. It's spicier than your average YA book, but then lines have gotten more and more blurred between YA and NA and adults romance, so... With Coal and Hex in college, this is largely a coming-of-age story; Coal has to figure out how to grow up and distinguish himself from his father (or rather, from Father Christmas), and, well...I think I'm going to carry on mentally treating this as YA.

At any rate, it's a basically cute story. The Red, White & Royal Blue comparison is bollocks, of course, but I guess when a book (an excellent book!) gets that much press, everyone wants it as a comp title. I think I'd have liked a bit more worldbuilding, and in particular an acknowledgement of non-Western holidays—

I won't go out of my way to read the next book, but if a future book in the series brings in some holidays I know less about, I'd consider jumping back in.

Thursday, May 15, 2025

Review: Short story: "The Bookstore Family" by Alice Hoffman

The Bookstore Family by Alice Hoffman

Published May 2025 via Amazon Original Stories

And we're back to the bookstore in Maine—well, first we're off to Paris, where Violet has been living for the past few years. She's found success, but it's clear (to Violet, even if she won't admit it, and to everyone who knows Violet) that she hasn't found what she's looking for, and that she doesn't know what that is.

This is the third of this short-story series that I've read (encompassing, still, the only Hoffman I've read). It's nice to see more of a character who was a bit on the periphery in earlier books—and of course I'll never object to a vicarious trip to Paris!

As with the other short stories in this series, this leans a little saccharine for my tastes. (Partly it's the pastry names, I think, and partly it's the insistence that everything can be solved with love—generally the romantic and heterosexual kind.) I can see why people like Hoffman, but I think I'm best off sticking to these bite-sized stories rather than digging into something longer.

One for those looking for something quick and cozy.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via Amazon Original Stories

And we're back to the bookstore in Maine—well, first we're off to Paris, where Violet has been living for the past few years. She's found success, but it's clear (to Violet, even if she won't admit it, and to everyone who knows Violet) that she hasn't found what she's looking for, and that she doesn't know what that is.

This is the third of this short-story series that I've read (encompassing, still, the only Hoffman I've read). It's nice to see more of a character who was a bit on the periphery in earlier books—and of course I'll never object to a vicarious trip to Paris!

As with the other short stories in this series, this leans a little saccharine for my tastes. (Partly it's the pastry names, I think, and partly it's the insistence that everything can be solved with love—generally the romantic and heterosexual kind.) I can see why people like Hoffman, but I think I'm best off sticking to these bite-sized stories rather than digging into something longer.

One for those looking for something quick and cozy.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

Review: "Wards of the State" by Claudia Rowe

Wards of the State by Claudia Rowe

Published May 2025 via Abrams Press

★★★★

By the time Maryanne was sixteen, she'd been arrested for murder. Rowe met her in the context of that trial: she was used to writing about murder and didn't think there would be anything special here—but then she started to hear the arguments about foster care.

In Wards of the State, Rowe dives deep into what happens when a child is removed from their family and placed in foster care. The statistics are dire:

A study of nearly one thousand foster youth in the Midwest found that half left the system with criminal records, and more than 30 percent were imprisoned for violent crime within a year of leaving state care. At least 20 percent of prison inmates nationally are believed to be former foster children. (loc. 70*)

Conventional wisdom holds that these kids are more likely to end up in prison (or without a diploma, or homeless, or otherwise just struggling) because of troubled family backgrounds—they struggle because of the reasons for which they were placed in foster care. But the more Rowe dug into it, the more she questioned that assumption, and the more the research seemed to support the opposite: foster care wasn't reducing trauma but rather compounding it. When a child is moved from placement to placement to placement—I'm not sure if an average number of moves was mentioned, but Rowe does cite cases of children who were moved fifty or more (sometimes many more) times in a year—how is that child expected to develop healthy attachments and relationships, to keep up in school, and to learn the basic life skills that aren't really taught but learned through observation and repetition?

There are a lot of questions here that just don't have good answers: at what point is it safer to leave a child in a home where neglect or abuse is suspected, and at what point is it safer to remove that child to a system that is stopgap after stopgap after stopgap? And how often does "neglect" (e.g., an empty fridge) simply mean "poverty"? And when the state-as-parent does cause harm, how much can it be held responsible? (Other questions have much clearer answers, such as those surrounding the deep racism embedded in foster care.)

This is compassionate and complex reportage. The people Rowe profiles—former foster children who have found themselves in places ranging from PhD programs to life sentences—are treated with a lot of care, withoug skating over their darker moments. (Whole people, in shades of grey.) What she describes is much in line with other things I have read about foster care and about group homes (some suggestions for further reading below), but very, very pointed.

I am a little unclear on how some of the statistics play out—for example, how often is a child who is placed in foster care returned to their family, and after an average of how long? How do the outcomes differ? What is the tipping point? And, more broadly: What are other countries doing, and does anyone seem to have figured it out? Rowe mentions a program in the New York that is based on a UK model—a program that seems brilliant until (as with so many of the possible fixes Rowe investigates) the cracks begin to show. But the biggest difference between the British version of Chelsea Foyer and New York City's showed up around education. The academic deficits among former foster youth in New York were severe [...] such that the requirement to be in school became a barrier. [...] Within a few years of opening, New York jettisoned the three-pronged European model of housing, education, and career, retooling to emphasize housing and employment only. (loc. 2670)

It's easy to look at this all and think "well, X would help"—but it becomes then a matter of "in order for X to happen, we'd need Y, for which we'd need Z, for which we'd need..." until you come back around to X. Maryanne's situation is one of the more high-profile of those Rowe includes. She was sentenced in 2019, but it seems that some parts of her case are ongoing. (Not getting more specific because how her case played out is a significant part of the book and worth reading in its entirety.) I couldn't find anything particularly recent online, but she's emblematic of a broken system that chews children up until they, too, leave broken.

Somewhere between 4 and 5 stars. Highly recommended.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Related books that readers might find interesting:

Home Made (group home)

How the Other Half Eats (food and poverty politics)

To the End of June (foster care)

No House to Call My Home (group home)

The Turnaway Study (abortion; poverty and body politics)

Published May 2025 via Abrams Press

★★★★

By the time Maryanne was sixteen, she'd been arrested for murder. Rowe met her in the context of that trial: she was used to writing about murder and didn't think there would be anything special here—but then she started to hear the arguments about foster care.

In Wards of the State, Rowe dives deep into what happens when a child is removed from their family and placed in foster care. The statistics are dire:

A study of nearly one thousand foster youth in the Midwest found that half left the system with criminal records, and more than 30 percent were imprisoned for violent crime within a year of leaving state care. At least 20 percent of prison inmates nationally are believed to be former foster children. (loc. 70*)

Conventional wisdom holds that these kids are more likely to end up in prison (or without a diploma, or homeless, or otherwise just struggling) because of troubled family backgrounds—they struggle because of the reasons for which they were placed in foster care. But the more Rowe dug into it, the more she questioned that assumption, and the more the research seemed to support the opposite: foster care wasn't reducing trauma but rather compounding it. When a child is moved from placement to placement to placement—I'm not sure if an average number of moves was mentioned, but Rowe does cite cases of children who were moved fifty or more (sometimes many more) times in a year—how is that child expected to develop healthy attachments and relationships, to keep up in school, and to learn the basic life skills that aren't really taught but learned through observation and repetition?

There are a lot of questions here that just don't have good answers: at what point is it safer to leave a child in a home where neglect or abuse is suspected, and at what point is it safer to remove that child to a system that is stopgap after stopgap after stopgap? And how often does "neglect" (e.g., an empty fridge) simply mean "poverty"? And when the state-as-parent does cause harm, how much can it be held responsible? (Other questions have much clearer answers, such as those surrounding the deep racism embedded in foster care.)

This is compassionate and complex reportage. The people Rowe profiles—former foster children who have found themselves in places ranging from PhD programs to life sentences—are treated with a lot of care, withoug skating over their darker moments. (Whole people, in shades of grey.) What she describes is much in line with other things I have read about foster care and about group homes (some suggestions for further reading below), but very, very pointed.

I am a little unclear on how some of the statistics play out—for example, how often is a child who is placed in foster care returned to their family, and after an average of how long? How do the outcomes differ? What is the tipping point? And, more broadly: What are other countries doing, and does anyone seem to have figured it out? Rowe mentions a program in the New York that is based on a UK model—a program that seems brilliant until (as with so many of the possible fixes Rowe investigates) the cracks begin to show. But the biggest difference between the British version of Chelsea Foyer and New York City's showed up around education. The academic deficits among former foster youth in New York were severe [...] such that the requirement to be in school became a barrier. [...] Within a few years of opening, New York jettisoned the three-pronged European model of housing, education, and career, retooling to emphasize housing and employment only. (loc. 2670)

It's easy to look at this all and think "well, X would help"—but it becomes then a matter of "in order for X to happen, we'd need Y, for which we'd need Z, for which we'd need..." until you come back around to X. Maryanne's situation is one of the more high-profile of those Rowe includes. She was sentenced in 2019, but it seems that some parts of her case are ongoing. (Not getting more specific because how her case played out is a significant part of the book and worth reading in its entirety.) I couldn't find anything particularly recent online, but she's emblematic of a broken system that chews children up until they, too, leave broken.

Somewhere between 4 and 5 stars. Highly recommended.

*Quotes are from an ARC and may not be final.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Related books that readers might find interesting:

Home Made (group home)

How the Other Half Eats (food and poverty politics)

To the End of June (foster care)

No House to Call My Home (group home)

The Turnaway Study (abortion; poverty and body politics)

Sunday, May 11, 2025

Review: "Falling for Korea" by Piper Jean

Falling for Korea by Piper Jean

Published June 2022 via Vaniker Press

★

That was...a ride. Untagged spoilers below the fold.

The cover: Is lovely.

The heroine, part 1: A blonde, blue-eyed California girl who is sent to Korea by her mother, who will not tell her why. Sydney's first language is, improbably, Korean (learned from her similarly white mother), and virtually nobody in Korea blinks at this. Despite speaking fluent and apparently unaccented Korean, has never heard of most Korean food and openly talks about American food as "real food". (Cue all the Korean boys falling over themselves to make sure she never has to eat Korean food.)

The heroine's friends: Nonexistent. I think the book technically does pass the Bechdel test, because there are other female characters and Sydney occasionally engages with them, but it passes only on a technicality. After all, why would a seventeen-year-old need friends when she has astalker godbrother boyfriend husband around to fulfill all her social needs?

The heroine's godparents: Running Sydney's life without any agreement from her or, like, telling her what they're doing. Have planned out her adoption, where she'll go to university, where she'll live, and who she'll marry...all while she still thinks she's returning to her mother in California in a few weeks.

Literally everyone but Sydney: Actively lying to Sydney for most of the book.

Villain #1: A mean bitchy mean bitchy meanie who is not above chucking a rock at someone's head or putting a terminally ill child's already shortened life at risk to make the (completely innocent, naturally) heroine look bad. Throws herself constantly at the hero (though everyone understands that she doesn't actually want him; she just wants him to want her). Runs rampant through the book, chucking rocks and all, until she drops off the page because there's a bigger villain in town.

Villain #2: Not actually the bigger villain (that one's still to come). One of the boys who immediately falls head over heels for Sydney for no particular reason except that she's there. Gets aggressive fast. Eventually sees the error of his ways and dedicates himself to protecting Sydney from villain #1...until she drops off the page and so does he.

The hero: One giant red flag. Is a literal stalker—puts tracking software on Sydney's phone before even meeting her, reads Sydney's emails, interferes with her emails, hacks her bank account, reads her text messages, etc., etc. Gets mad and tells Sydney she is "too emotional" when she's upset at learning the truth about the first of his lies. By the time we get to lie #713, she's thinking that "only Chul could make stalking romantic" (185). IT IS NOT ROMANTIC, SYDNEY. HE'S AN ASSHOLE. Also low-key tries to guilt Sydney into sex, after she has been married to him without her knowledge or agreement, by asking how much more sure she can be than married. SHE DIDN'T AGREE TO MARRY YOU, YOU ASSHOLE.

The heroine, part 2: A doormat. One who feels guilty that the guy who forced her to marry him is now stuck with her.

Villain #3: On paper he has Munchausen by proxy (albeit a manifestation that I don't think exists in real life). In practice he's just unhinged.

The plot: Also unhinged.

I don't know what I expected out of the book, but this was not it. If I'd ever seen a K-drama, would this all make more sense? I'm not sure I've ever seen even an American soap opera. Though, if Chul is the sort of hero one can expect in a soap opera—from any country—then nope, nope, I'm out. Nobody needs that many red flags in their life.

Published June 2022 via Vaniker Press

★

That was...a ride. Untagged spoilers below the fold.

The cover: Is lovely.

The heroine, part 1: A blonde, blue-eyed California girl who is sent to Korea by her mother, who will not tell her why. Sydney's first language is, improbably, Korean (learned from her similarly white mother), and virtually nobody in Korea blinks at this. Despite speaking fluent and apparently unaccented Korean, has never heard of most Korean food and openly talks about American food as "real food". (Cue all the Korean boys falling over themselves to make sure she never has to eat Korean food.)

The heroine's friends: Nonexistent. I think the book technically does pass the Bechdel test, because there are other female characters and Sydney occasionally engages with them, but it passes only on a technicality. After all, why would a seventeen-year-old need friends when she has a

The heroine's godparents: Running Sydney's life without any agreement from her or, like, telling her what they're doing. Have planned out her adoption, where she'll go to university, where she'll live, and who she'll marry...all while she still thinks she's returning to her mother in California in a few weeks.

Literally everyone but Sydney: Actively lying to Sydney for most of the book.

Villain #1: A mean bitchy mean bitchy meanie who is not above chucking a rock at someone's head or putting a terminally ill child's already shortened life at risk to make the (completely innocent, naturally) heroine look bad. Throws herself constantly at the hero (though everyone understands that she doesn't actually want him; she just wants him to want her). Runs rampant through the book, chucking rocks and all, until she drops off the page because there's a bigger villain in town.

Villain #2: Not actually the bigger villain (that one's still to come). One of the boys who immediately falls head over heels for Sydney for no particular reason except that she's there. Gets aggressive fast. Eventually sees the error of his ways and dedicates himself to protecting Sydney from villain #1...until she drops off the page and so does he.

The hero: One giant red flag. Is a literal stalker—puts tracking software on Sydney's phone before even meeting her, reads Sydney's emails, interferes with her emails, hacks her bank account, reads her text messages, etc., etc. Gets mad and tells Sydney she is "too emotional" when she's upset at learning the truth about the first of his lies. By the time we get to lie #713, she's thinking that "only Chul could make stalking romantic" (185). IT IS NOT ROMANTIC, SYDNEY. HE'S AN ASSHOLE. Also low-key tries to guilt Sydney into sex, after she has been married to him without her knowledge or agreement, by asking how much more sure she can be than married. SHE DIDN'T AGREE TO MARRY YOU, YOU ASSHOLE.

The heroine, part 2: A doormat. One who feels guilty that the guy who forced her to marry him is now stuck with her.

Villain #3: On paper he has Munchausen by proxy (albeit a manifestation that I don't think exists in real life). In practice he's just unhinged.

The plot: Also unhinged.

I don't know what I expected out of the book, but this was not it. If I'd ever seen a K-drama, would this all make more sense? I'm not sure I've ever seen even an American soap opera. Though, if Chul is the sort of hero one can expect in a soap opera—from any country—then nope, nope, I'm out. Nobody needs that many red flags in their life.

Friday, May 9, 2025

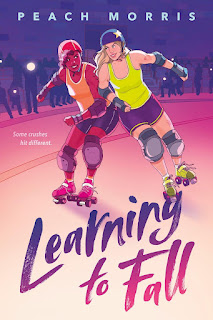

Review: "Learning to Fall" by Peach Morris

Learning to Fall by Peach Morris

Published May 2025 via 8th Note Press

★★★★

When Casey catches her boyfriend in bed with someone else, her summer plans go up in smoke—but she almost immediately finds something much better. Before she knows it, she's training for a sport she didn't know existed, and taking spontaneous day trips, and expanding her social circle beyond what she could have imagined. But those things can't stop her anxiety at the thought of leaving her mother behind for uni in a year, and they can't tell her what to do about the feelings she's caught for a teammate.

I don't want to play roller derby (I like my osteopenic bones intact), but gosh it's fun to watch, and fun to read about. I knew from the first couple of scenes that this was going to be a good one: so many books that open with the POV character catching their partner in bed with someone else immediately spiral off into drama and bad decisions, and I loved seeing Casey be so...rational about it, I guess. Not happy, but rational. Seriously underrated, that.

Other things that are nice to see: how matter-of-fact Casey is about taking care of her mother. Chronic illness that's presented in a way that just is—not a good thing, and sometimes a source of worry, but not a source of drama. A romance that goes in unexpected directions. I don't want to say too much about the plot or the various sources of tension, because they're better unfolding as you go, but this is an excellent addition to the slowly growing library of roller derby books out there, and an excellent debut.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Published May 2025 via 8th Note Press

★★★★

When Casey catches her boyfriend in bed with someone else, her summer plans go up in smoke—but she almost immediately finds something much better. Before she knows it, she's training for a sport she didn't know existed, and taking spontaneous day trips, and expanding her social circle beyond what she could have imagined. But those things can't stop her anxiety at the thought of leaving her mother behind for uni in a year, and they can't tell her what to do about the feelings she's caught for a teammate.

I don't want to play roller derby (I like my osteopenic bones intact), but gosh it's fun to watch, and fun to read about. I knew from the first couple of scenes that this was going to be a good one: so many books that open with the POV character catching their partner in bed with someone else immediately spiral off into drama and bad decisions, and I loved seeing Casey be so...rational about it, I guess. Not happy, but rational. Seriously underrated, that.

Other things that are nice to see: how matter-of-fact Casey is about taking care of her mother. Chronic illness that's presented in a way that just is—not a good thing, and sometimes a source of worry, but not a source of drama. A romance that goes in unexpected directions. I don't want to say too much about the plot or the various sources of tension, because they're better unfolding as you go, but this is an excellent addition to the slowly growing library of roller derby books out there, and an excellent debut.

Thanks to the author and publisher for providing a review copy through NetGalley.

Wednesday, May 7, 2025

Review: "A Sharp Endless Need" by Marisa Crane

A Sharp Endless Need by Marisa Crane

Published May 2025 via The Dial Press

★★★

It was as if we'd been playing together our entire lives. We didn't even have to say anything; we knew when the other's blood was hot with fury. We were alone together; we were a crowd all our own. We were ethereal; we were of the world. We were untouchable; we were touching each other all the time, with every pass, every play, every time-out, every steal. (loc. 1339*)

Another time and another place: When Mack and Liv meet, it's an instant connection. They're both basketball players with Division I dreams and the skills to back it up. The air sizzles between them, on and off the court. But: It's a different time. Liv has a boyfriend; heterosexuality is the only option that has ever been modelled for them; Mack, too, is unwilling to take that first step out of bounds.